Enter the Jaguar

The monumental ruins of Chavín de Huantar, ten thousand feet up in the Cordillera Blanca of the Peruvian Andes, are, officially, a mystery. The vast, ruined granite and sandstone structures – cyclopean walls, huge sunken plazas and step pyramids – date from around 1000BC but, although they were refashioned and augmented for close to a thousand years, the evidence for the material culture associated with them is fragmentary at best. Chavín seems to have been neither a city nor a military structure, but a temple complex constructed for unknown ritual purposes by a culture which had vanished long before written sources appeared. Its most striking feature is that its pyramids are hollow, a labyrinth of tunnels connecting hundreds of cramped stone chambers. These might be tombs, but there are no bodies; habitations, but they’re arranged in a disorienting layout in pitch blackness; grain stores, but their arrangement is equally impractical. Instead, there are irrigation ducts honeycombed through the carved rock, elaborately channeling a nearby spring through the subterranean maze, and in the centre a megalith set in a vaulted chamber and carved with a swirling, baroque representation of a huge-eyed and jaguar-fanged entity.

The archaeological consensus is that Chavín was some kind of ceremonial focus; some have tentatively located it within a lost tradition of oracles and dream incubation. But the mystery remains profound, and the questions at stake are considerable. By most reckonings, and depending on how the term is defined, ‘civilisation’ emerged spontaneously in only a handful of locations around the globe: Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley, China, Mexico, perhaps the Nile. To this short list, especially if civilisation is defined in terms of monumental architecture, must now be added Peru. It was only proposed in the 1930s that Chavín is three thousand years old, and it has only recently been recognised that huge ceremonial structures of plazas and pyramids were being constructed in Peru at least a thousand years earlier. The coastal site of Caral, only now being excavated, turns out to contain the oldest stone pyramid thus far discovered, predating those of Old Kingdom Egypt. So the mystery of Chavín is nested inside a larger one: the flowering of a pristine and unique culture that still awaits interpretation.

But there is a salient and little examined feature of the Chavín culture that offers a lead into the heart of the mystery: the presence of plant hallucinogens in its ritual world. The San Pedro cactus (Echinopsis peruvianus) is explicitly featured in its iconography; like the Mexican peyote cactus, San Pedro contains mescaline, and is still widely used as a visionary intoxicant in Peru today. Objects excavated from the site also include snuff trays and bone tubes similar to those still used in the Peruvian Amazon for inhaling seeds and barks containing the powerful hallucinogen dimethyltryptamine (DMT). The leading Western scholar of the culture, Yale University’s Richard Burger, whose Chavín and the Origins of Andean Civilisation (Thames & Hudson 1992) is the most authoritative survey of the territory, states plainly enough that ‘the central role of psychotropic substances at Chavín is amply documented’.

But there is a salient and little examined feature of the Chavín culture that offers a lead into the heart of the mystery: the presence of plant hallucinogens in its ritual world. The San Pedro cactus (Echinopsis peruvianus) is explicitly featured in its iconography; like the Mexican peyote cactus, San Pedro contains mescaline, and is still widely used as a visionary intoxicant in Peru today. Objects excavated from the site also include snuff trays and bone tubes similar to those still used in the Peruvian Amazon for inhaling seeds and barks containing the powerful hallucinogen dimethyltryptamine (DMT). The leading Western scholar of the culture, Yale University’s Richard Burger, whose Chavín and the Origins of Andean Civilisation (Thames & Hudson 1992) is the most authoritative survey of the territory, states plainly enough that ‘the central role of psychotropic substances at Chavín is amply documented’.

These mind-altering plants offer a clue to the mysteries by indicating the state of consciousness in which they would have taken place. They also open up the collateral evidence of the ways in which these plants are still used in the region, and the modern knowledge of the drugs they contain. The combination of mescaline- and DMT-containing plants has been surprisingly little explored in contemporary drug subculture but they are readily (and often legally) obtainable, and can be prepared in powerfully psychoactive doses. The experiences they generate in modern subjects have limited explanatory power: there is no way of extrapolating how they would have been perceived or understood in far distant times and cultures. But even if they offer no evidence for the content of the ceremonies in which they were used, the effects of these particular substances set logistical parameters for their use, to which the design of the Chavín complex may have been a practical response.

So: first, a brief survey of the culture from which Chavín emerged, followed by some thoughts on the role that plant hallucinogens might have played in the temple’s mysteries.

For many thousands of years the Pacific coast of Peru has been as it is today: a barren, moonscape desert. Rain never falls except in El Niño years; fresh water is only to be found in the few river valleys that punctuate it; for the best part of a thousand miles, rocky shores meet cold ocean in a misty haze. But the harsh terrain has its riches: the Humboldt current, sweeping up from the freezing depths of the southern ocean, is loaded with krill and alive with fish, its biomass a hundred times greater than the balmy Atlantic at the same latitude off Brazil. For ten thousand years a substantial human population has been sustained by this current: foul-smelling industrial fish-meal factories today, but since deep prehistory itinerant hunter-gatherers whose presence is attested by massive shell middens. Some of these hills of organic detritus – oyster shells, cotton twine, dried chillis, crushed bones – are a hundred feet high, and were in continuous use for five thousand years or more.

It was out of this seasonally nomadic coastal culture, moving between the arid coasts and the fertile mountain valleys, that the first monumental sites emerged. Dates are still being revised, but are now firmly set some time before 2000BC. The sites may have been used much earlier as huacas, natural sacred spots, around which ceremonial stone  and adobe structures gradually accreted and expanded. Caral, a massive site a hundred miles north of Lima where substantial excavation is finally under way, is an early example of this process. Its sprawling complex of dusty mounds centres on a megalith, perhaps originally upended into the valley by an earthquake; from the vantage point of this stone the oldest pyramid fits precisely beneath the peak of the mountain that towers over it, suggesting that the megalith may have been the original focus for this alignment. The pyramids, at Caral as elsewhere, seem to have begun as raised platforms for fire-pits, subsequently extended upward in layers as the site grew to accomodate increasing human traffic. Below Caral’s pyramids is another feature that would endure for millennia and spread from the coast to the high mountains: a sunken circular plaza, large enough for a gathering of several hundred participants, with steps leading up to the platform of the pyramid above.

and adobe structures gradually accreted and expanded. Caral, a massive site a hundred miles north of Lima where substantial excavation is finally under way, is an early example of this process. Its sprawling complex of dusty mounds centres on a megalith, perhaps originally upended into the valley by an earthquake; from the vantage point of this stone the oldest pyramid fits precisely beneath the peak of the mountain that towers over it, suggesting that the megalith may have been the original focus for this alignment. The pyramids, at Caral as elsewhere, seem to have begun as raised platforms for fire-pits, subsequently extended upward in layers as the site grew to accomodate increasing human traffic. Below Caral’s pyramids is another feature that would endure for millennia and spread from the coast to the high mountains: a sunken circular plaza, large enough for a gathering of several hundred participants, with steps leading up to the platform of the pyramid above.

This plaza-and-pyramid layout, reproduced in dozens of sites spanning hundreds of miles and thousands of years, seems to have evolved for a ceremonial purpose, but there is little consensus about what this might have entailed. Beyond the general problem of reconstructing systems of meaning and belief from stone, these early sites are sparse in cultural materials. Graves are few, and simple; the early monumental building predates the firing of pottery (hence the archaeological term for the era, ‘Preceramic’). There is little general evidence of human habitation, although there are some chambers in the Caral pyramids which may have housed those who attended the site. Some scholars have sought to cast these as a ‘priestly elite’, the ruling caste of a stratified society, but they may equally have been no more than a class of specialist functionaries without particularly exalted status in the community. Certainly a site like Caral would have been no prize residence. It is not a palace at the centre of a subjugated settlement so much as a monastic perch on its desolate fringes. Its barren, windswept desert setting overlooks the fertile valley, taking up none of the precious irrigated terrain.

The size of the complex suggests that the fertile valley attracted visitors, and that Caral was a site of pilgrimage for more than its local community. The earliest agriculture on the coast emerged in such valleys, especially cotton and gourds, which were used for making fishing nets and floats: it may be, therefore, that the ceremonial site grew in size as the use of these cultivated commodities spread through the loose network of fishing communities up and down the coast. This would suggest a very different picture from that presented by better-known pristine civilisations such as Mesopotamia or the Indus Valley, where archaeologists have tended to associate the origins of monumental architecture with centralised control: a unitary state, coercive labour, irrigation systems, a powerful priestcraft or military might. Peru seems to tell a contrasting story of structures emerging largely unplanned, piecemeal and over generations, within a shifting, stateless network of hunter-gatherers.

A further clue to the culture of these Preceramic coastal sites is provided by Sechin, a complex a few centuries later than Caral (around 1700BC) and a couple of river valleys to the north. Here, for the first time, the temple is adorned with figurative carvings; but if these are a clue, they are an oblique one. Cut in relief into large stone blocks, most are of human forms, some dismembered, with the distinctive motif of wavy trail lines, often ending in finger-like tips, emanating from various parts of the bodies. Some of these seem to be intestines, and some emerge from the mouths of the carvings, but others coil from heads, hands and ears, suggesting they are not literal representations of blood, guts or bodily fluids. Their significance remains disputed. Early interpretations tended to make them warrior figures commemorating battles and annihilated populations, but many of the figures are hard to fit into such a scheme. Recent interpretations, by contrast, have tended to focus on visionary, perhaps shamanic states, with the numinous swirls and haloes commemorating not violent conflict but the cosmic mysteries that ceremonies at Sechin engendered.

A further clue to the culture of these Preceramic coastal sites is provided by Sechin, a complex a few centuries later than Caral (around 1700BC) and a couple of river valleys to the north. Here, for the first time, the temple is adorned with figurative carvings; but if these are a clue, they are an oblique one. Cut in relief into large stone blocks, most are of human forms, some dismembered, with the distinctive motif of wavy trail lines, often ending in finger-like tips, emanating from various parts of the bodies. Some of these seem to be intestines, and some emerge from the mouths of the carvings, but others coil from heads, hands and ears, suggesting they are not literal representations of blood, guts or bodily fluids. Their significance remains disputed. Early interpretations tended to make them warrior figures commemorating battles and annihilated populations, but many of the figures are hard to fit into such a scheme. Recent interpretations, by contrast, have tended to focus on visionary, perhaps shamanic states, with the numinous swirls and haloes commemorating not violent conflict but the cosmic mysteries that ceremonies at Sechin engendered.

There is some evidence that psychoactive plants may have played a role in these ceremonial cultures, in the era before they were first explicitly represented at Chavín. Coastal sites near Sechin have yielded chewed coca leaf quids and rolls of plant material that may be cored, skinned and dried San Pedro cactus. The coca implies that a trade network was already extant between the coast and the mountains: coca does not grow on the coast, but at an altitude of 1000-2000m up the mountain valleys. The San Pedro cactus begins to colonise the steep mountain cliffs at the upper end of this belt, continuing up to around 3000m. Given that more bulky mountain plant foodstuffs were being supplied to the barren desert coast two or three days’ journey away and dried and salted fish traded in return, it is plausible that fresh or dried San Pedro could have been brought down in quantity, as it still is today.

By the time of Sechin there were already ceremonial centres in the mountains. The Preceramic site of Kotosh, a hundred miles away from it across the inland ranges, dates from a similar period and contains similar structures: altar-like  platforms around stone-enclosed fire pits, stacked on top of one another through several layers of occupation. One gnomic Preceramic symbol also survives: a moulded mud-brick relief of a pair of crossed hands, now housed in the national museum in Lima. Centuries before Chavín, perhaps as early as 2000BC, Kotosh demonstrates that trade links between the mountains and the coast had generated some commonality of worship.

platforms around stone-enclosed fire pits, stacked on top of one another through several layers of occupation. One gnomic Preceramic symbol also survives: a moulded mud-brick relief of a pair of crossed hands, now housed in the national museum in Lima. Centuries before Chavín, perhaps as early as 2000BC, Kotosh demonstrates that trade links between the mountains and the coast had generated some commonality of worship.

The emergence of Chavín as a ceremonial centre, probably around 900BC, adds much to this archaic picture. It is more complex in construction than its predecessors, and far richer in symbolic art. It is not set on an imposing peak but within the narrow valley of the Mosna river, at the junction of a tributary, mountains rising up steeply to enclose it on all sides. The temple structures are not visible from any distance, but concealed from all sides behind high walls. The approach would have been through a narrow ramped entrance in these walls, studded with gargoyle-like, life-size heads, some human, some distinctly feline with exaggerated jaws and sprouting canine teeth, and some, often covered in swirling patterns, in the process of transforming from one state to the other. This process of transformation is clearly a physical ordeal: the shapeshifting heads grimace, teeth exposed in rictus grins. In a specific and recurrent detail, mucus emanates in streams from their noses.

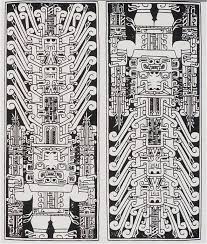

Inside these walls – now mostly crumbled, and with the majority of the heads housed in the on-site museum – there are still substantial remains of a ceremonial complex that was reworked and expanded for nearly a thousand years, its last and largest elements dating to around 200BC. The basic arrangement was the by now traditional plaza and step pyramid, but these were far more highly adorned than earlier sites: lintels, columns and stelae are covered with relief carvings, swirling motifs featuring feline jaws, eyes and wings. The initial impression is amorphous and chaotic, but on closer inspection the motifs unfurl into composite images, their elements reading in multiple scales and dimensions, and the whole often representing an chimera composed of smaller-scale entities roiling inside it. As the architecture developed through the centuries it became larger, reflecting the increased scale of the site, while the reliefs gradually become less figurative and more abstract, melting into a mosaic of stylised patterns and flourishes.

Inside these walls – now mostly crumbled, and with the majority of the heads housed in the on-site museum – there are still substantial remains of a ceremonial complex that was reworked and expanded for nearly a thousand years, its last and largest elements dating to around 200BC. The basic arrangement was the by now traditional plaza and step pyramid, but these were far more highly adorned than earlier sites: lintels, columns and stelae are covered with relief carvings, swirling motifs featuring feline jaws, eyes and wings. The initial impression is amorphous and chaotic, but on closer inspection the motifs unfurl into composite images, their elements reading in multiple scales and dimensions, and the whole often representing an chimera composed of smaller-scale entities roiling inside it. As the architecture developed through the centuries it became larger, reflecting the increased scale of the site, while the reliefs gradually become less figurative and more abstract, melting into a mosaic of stylised patterns and flourishes.

It was only in 1972 that the most striking of these reliefs was uncovered, on faced slabs which line the ol dest of the sunken plazas, running like a frieze around its circle at knee height. These figures are presumably from the site’s formative period; the most remarkable is a human figure in a state of feline transformation, bristling with jaws, claws and snakes, and clutching an unmistakable San Pedro cactus like a staff or spear. Beneath this figure – the ‘Chaman’, as he’s become informally known – runs a procession of jaguars carved in swirling lines, with other creatures, birds of prey and snakes, sometimes incorporated into the whorls of their tails.

dest of the sunken plazas, running like a frieze around its circle at knee height. These figures are presumably from the site’s formative period; the most remarkable is a human figure in a state of feline transformation, bristling with jaws, claws and snakes, and clutching an unmistakable San Pedro cactus like a staff or spear. Beneath this figure – the ‘Chaman’, as he’s become informally known – runs a procession of jaguars carved in swirling lines, with other creatures, birds of prey and snakes, sometimes incorporated into the whorls of their tails.

These reliefs are all carved in profile, and all face towards the steps that lead up from the circular plaza to the old pyramid, at the top of which is the familiar altar-like platform. But at the back of this platform is something entirely unfamiliar: a pair of stone doorways disappearing into the darkness inside the pyramid itself. These lead via steps down into tunnels around six foot high, constructed from huge granite slabs and lintels. The tunnels take sharp, maze-like, usually right-angled turns, apparently designed to disorient and cut out the daylight, zig-zagging into pitch blackness. Opening out from these subterranean corridors are dozens of rock-hewn side chambers, some large enough for half a dozen people, others seemingly for solitary confinement. There are niches hacked in some of the chamber walls that might have housed oil lamps, and lintels that extrude like hammock pegs. Running through the bewildering network of tunnels and chambers are smaller shafts, some of them air vents, others water ducts that allowed the waters of a spring to gush and echo through this elaborately constructed underworld.

Opening out from these subterranean corridors are dozens of rock-hewn side chambers, some large enough for half a dozen people, others seemingly for solitary confinement. There are niches hacked in some of the chamber walls that might have housed oil lamps, and lintels that extrude like hammock pegs. Running through the bewildering network of tunnels and chambers are smaller shafts, some of them air vents, others water ducts that allowed the waters of a spring to gush and echo through this elaborately constructed underworld.

Right in the heart of the labyrinth is a stela carved in the early Chavín style, a clawed, fanged and rolling-eyed humanoid form, boxed inside a cramped cruciform chamber which rises to the top of the pyramid. The loose arrangement of stones in the roof above, which form a plug at the crown of the pyramid, have led to speculation that they might have been removable, allowing the Lanzon, as the carved stela is known, to point up like a needle to a gap of exposed sky. Other fragments of evidence from the site, such as a large boulder with seven sunken pits in the configuration of the Pleiades, suggest that an element of the Chavín ritual – perhaps, given the narrow confines around the Lanzon, a priestly rather than a public one – might have involved aligning the stela with astronomical events.

This plaza and pyramid was Chavín’s original structure, to which over the centuries more and grander structures were added. There are several shafts, some still unexcavated, which lead down into larger underground complexes, their stonework more regular than the old pyramid and their side-chambers typically more spacious. There is a far larger sunken plaza, too, square rather than circular and leading up to a newer pyramid and surrounding walls on a monumental scale. Whatever happened at Chavín, the architecture suggests that it carried on happening for centuries, and for an increasing volume of participants.

The term most commonly applied to what went on at Chavín is ‘cult’, although its meaning might be qualified by other terms such as pilgrimage destination, sacred site, oracle or, in its classical sense, temple of mysteries. This conclusion is partly drawn from lack of evidence that it wielded any form of state power: there are no military structures associated with it, nor centralised labour for major public works, nor large-scale habitations. During the several centuries of its existence, tribal networks of dominance rose and fell around it, leaving its source of authority seemingly untouched. Yet its cultural, or cultic, influence spread far and wide. Throughout the first millennium BC, ‘Chavínoid’ sites appeared across large swathes of northern Peru, and pre-existing natural huacas began to develop Chavín-style flourishes: rock surfaces carved with snaky fangs and jaws, standing stones decorated with bug-eyed, fierce-toothed humanoid forms. People were clearly coming to Chavín from considerable distances, and carrying its influence back to far-flung valleys, mountains and coasts.

across large swathes of northern Peru, and pre-existing natural huacas began to develop Chavín-style flourishes: rock surfaces carved with snaky fangs and jaws, standing stones decorated with bug-eyed, fierce-toothed humanoid forms. People were clearly coming to Chavín from considerable distances, and carrying its influence back to far-flung valleys, mountains and coasts.

Was Chavín, then, a religion? There has been much speculation that the carvings on the site represent a ‘Chavín cosmology’, with eagle, snake and jaguar corresponding to earth and sky and so forth, and the humanoid shapeshifter, as represented on the Lanzon, a ‘supreme deity’. But Chavín was not a power that could coerce its subjects to replace their religion with its own: the spread of its influence indicates that it drew its devotees from a wide range of belief systems with which it existed in parallel. It is perhaps better understood as a site that offered an experience rather than a cosmology or creed, its architecture conceived and designed as the locus for a particular ritual journey. In this scenario the Chavín figures would not have been deities competing with those of the participants, but graphic representations of the process which took place inside its walls.

The central motif of this process is signalled clearly enough by the shapeshifting feline heads that studded its portals: transformation from the human state into something else. It is here that Chavín displays the influence of a new cultural element not detectable in the sites that preceded it. The prominence of the jaguar and shapeshifting motifs suggest the intertwining of traditions not just from the coast and the mountains, but also from the jungle on the far side of the Andes. While the monumental style of Chavín’s architecture builds on earlier coastal models, this strand of its symbolism points towards the feline transformations that still chararacterise many Amazon shamanisms. The trading networks on the Pacific coast had long been joined with those in the mountains; at Chavín, where the river Mosna runs east into the Rio Marañon and thence into the Amazon, it seems that these networks had also reached down the humid eastern Andean slopes into the jungle, and had absorbed the influence of another culture: one characterised by powerful shamanic technologies of transformation, in many cases with the use of plant hallucinogens.

These twin influences – the coastal mountains and the jungle – are mirrored by the presence at Chavín of two hallucinogenic plants. The San Pedro cactus, as depicted on the wall of Chavín’s old plaza, may have been an element of the earlier coastal tradition but is native to Chavín’s high valley: a magnificent specimen which must be at least 200 years old towers over the site today. Local villages still plant hedges with it, and traders to the curandero markets down in the coastal cities still source it from the area. But the mucus pouring from the noses of the carved heads, combined with material finds of bone sniffing tubes and snuff trays, all point with equal clarity to the use at Chavín of plants containing a second plant intoxicant, DMT, a tradition with its source in the Amazon jungle.

The best known users of DMT-containing snuffs today are the Yanomami people of the Amazon, who traditionally blow powdered Virola tree bark resin up each others’ noses with six-foot blowpipes, producing a short and intense hallucinatory episode accompanied by spectacular streams of mucus. Other DMT-containing snuffs include the powdered seeds of the tree Anadenanthera colubrina whose distribution, and its artistic depiction in later Andean cultures, makes it the most likely to have been used at Chavín. Anadenanthera-snuffing has been replaced in many areas of the Amazon by ayahuasca-drinking, a more manageable technique of DMT ingestion, but this displacement is a relatively recent one and Anadenanthera is still used by some groups in the remote forest around the borders of Peru, Colombia and Brazil. Even today, the tree grows up the Amazonian slopes of the eastern Andes and as far west as the highlands around Kotosh.

The presence of these two plants at Chavín, without necessarily illuminating the purpose or content of the rituals, has certain implications. The effects and duration of San Pedro and Anadenanthera are very different from one another, and lend themselves to distinct ritual uses. San Pedro, boiled, stewed and drunk, can take an hour or more before the effects are felt; once they appear, they last for at least ten. The physical sensation is euphoric, languid, expansive, often with some accompanying nausea; in many Indian traditions, the effects are harnessed by setting the participants to slow, shuffling three-step dances and chants. The effect on consciousness is similarly fluid and oceanic, including visual trails and a heightened sense of presence: the swirling lines that surround the figures at Sechin could perhaps be interpreted as visual representations of this sense of energy projecting itself from the body – particularly from the swirling, psychedelicised intestines – into an immanent spirit world.

Anadenanthera, by contrast, is a short sharp shock, and powerfully potentiated by a prior dose of San Pedro. At least a gramme of powdered seed needs to be snuffed, enough to pack both nostrils. This rapidly elicits a burning sensation, extreme nausea and often convulsive vomiting, the production of gouts of nasal mucus and perhaps  half an hour of exquisite visions, often accompanied by physical contortions, growls and grimaces that are typically understood in Amazon cultures as feline transformations. Unlike San Pedro, which can be taken communally, the physical ordeal of Anadenanthera tends to make it a solitary one, the subject hunched in a ball, eyes closed, absorbed in a dazzling interior world. This world is perhaps recognisable in the new decorative elements that emerge at Chavín. Images such as the spectacular glyph that covers the Raimundi stela – a human figure which seems to be flowering into other dimensions and sprouting an elaborate headdress of multiple eyes and fangs – are reminiscent not just of ayahuasca art in the Amazon today but also of the highly elaborated fractal styles associated with DMT in modern Western subcultures.

half an hour of exquisite visions, often accompanied by physical contortions, growls and grimaces that are typically understood in Amazon cultures as feline transformations. Unlike San Pedro, which can be taken communally, the physical ordeal of Anadenanthera tends to make it a solitary one, the subject hunched in a ball, eyes closed, absorbed in a dazzling interior world. This world is perhaps recognisable in the new decorative elements that emerge at Chavín. Images such as the spectacular glyph that covers the Raimundi stela – a human figure which seems to be flowering into other dimensions and sprouting an elaborate headdress of multiple eyes and fangs – are reminiscent not just of ayahuasca art in the Amazon today but also of the highly elaborated fractal styles associated with DMT in modern Western subcultures.

The distinct effects of these two drugs suggests a functional division between two elements or phases of the ritual, and a rationale for Chavín’s contrasting architectural elements. Like the kiva in Southwestern Native American architecture which it so closely resembles, the circular plaza is readily interpreted as a communal space for large gatherings and celebrations, perhaps dancing and chanting through a long ritual accompanied by group intoxication with San Pedro: it may be that the cactus was already a traditional element of the coastal ceremonies where the form of the plaza originated. The innovative addition of chambers inside the pyramid, by contrast, seems designed for absorbtion in the interior world engendered by Anadenanthera, an incubation where the subject is transformed and reborn in the womb of darkness.

Chavín’s architecture, in this sense, can be understood as a visionary technology, designed to frame and intensify these effects and to focus them into a particular experience. This suggests an explanation for why so many might have made such long and arduous pilgrimages to its ceremonies. It was not necessary to visit Chavín simply to obtain San Pedro or Anadenanthera: both grow wild and abundantly in the Andes, and there could hardly have been a priestly monopoly on supply. Those who came to Chavín were not coerced into doing so: it drew participants from a wide area over which it exercised no political or military control. But its ceremony could have offered a unique ritual on a spectacular scale, where the visionary state engendered by the plants could be experienced en masse within an architecture designed to enhance and focus it.

Within this environment, participants could congregate to enter a shared otherworld, while also submitting themselves to a highly charged individual vision quest. The sunken plaza might, as the reliefs suggest, have harnessed San Pedro intoxication to a mass ritual of dancing and chanting, during which the participants might have ascended the temple steps individually to receive a further sacrament: powdered Anadenanthera seeds administered to them by the priests via bone snuffing tubes. As the snuff took hold, they could be led into the chambers within the pyramid to experience their DMT-enhanced visions in solitary darkness. Here, the amplified rushing of water and the growls and roars of the unseen participants around them would enclose them in a supernatural world beyond the limits of ordinary consciousness, where the body metamorphosed and the world could be glimpsed seen from an enhanced, superhuman perspective, analogous to the uncanny night vision of the feline predator. The expansion of the subterranean chambers over centuries would reflect the logistical demands of ever greater numbers of participants wishing to enter the jaguar portal and submit themselves to a life-changing ordeal that offered a glimpse of the eternal world beyond the human.

So Chavín remains a mystery, but perhaps in a more specific sense. If we want an analogy for its function drawn from Western culture, it might be the Eleusinian Mysteries, originating as they did in subterranean chambers near Athens a little later than Chavín, around 700BC. Like Chavín, Eleusis persisted for nearly a thousand years, under different empires, in its case Greek and Roman; like Chavín – and like the Haj at Mecca today – it was a pilgrimage site that drew its participants from a diverse network of cultures spanning virtually the known world. Classical written sources attest to some of the exterior details of the Eleusinian mysteries: its seasonal calendar, its processions, the ritual fasting and the breaking of the fast with a sacred plant potion, the kykeon. But over the thousand years that the mysteries endured, the deepest secrets of Eleusis – the visions that were revealed by the priestesses in the chambers in the bowels of the earth – were never revealed, protected under penalty of death. At Chavín the only surviving records are the stones of the site itself, but the mystery is perhaps of the same order.

Earlier versions of this article have appeared in Strange Attractor Journal Vol.2 (2005), South American Explorer (2006), Fortean Times (2005) Kadath (2007, in French), New Dawn Magazine (2010) and Entheogens and the Development of Culture (2013).

RELATED BOOKS: Blue Tide, High Society