The Rites of Roerich

The most familiar story of Rite of Spring‘s origins is Igor Stravinsky’s own: that it came to him in a waking dream or, as he put it, a “fleeting vision”. “I saw in imagination”, he recalled, “a solemn pagan rite: sage elders, seated in a circle, watched a young girl dance herself to death. They were sacrificing her to propitiate the gods of spring.” But by the time Stravinsky published this recollection in 1935 not only had he already told several contradictory variants on the story, but there was another man claiming that the original inspiration had been his: Nicholas Roerich, who had designed the sets and costumes for the original production of the ballet in 1913. At that time the relationship between Stravinsky and Roerich had been one not of rivalry but of conspiratorial, even feverish collaboration on the implausible-sounding idea  of a ballet set in the Stone Age: as Roerich described it at the time, “a reincarnation of antiquity”. Roerich was already known as the only man in Russia for such a task: in the words of a fellow artist, he was “utterly absorbed in dreams of prehistoric life… strangely susceptible to the primordial and weird charms of the ancient world”. This was the world that Roerich would bring to life in Rite of Spring, but his collaboration with Stravinsky would be only the beginning of a quest that would grow to occupy the rest of his life, taking him far beyond theatre and ballet and ultimately to the Himalayas, where he would discover that the origins of this ancient world were even stranger than he had imagined.

of a ballet set in the Stone Age: as Roerich described it at the time, “a reincarnation of antiquity”. Roerich was already known as the only man in Russia for such a task: in the words of a fellow artist, he was “utterly absorbed in dreams of prehistoric life… strangely susceptible to the primordial and weird charms of the ancient world”. This was the world that Roerich would bring to life in Rite of Spring, but his collaboration with Stravinsky would be only the beginning of a quest that would grow to occupy the rest of his life, taking him far beyond theatre and ballet and ultimately to the Himalayas, where he would discover that the origins of this ancient world were even stranger than he had imagined.

It was the creation of Rite of Spring that brought Roerich and Stravinsky together, but Roerich and Sergei Diaghilev had known each other for some years. Both had sat on the editorial board of the sumptuous avant-garde journal World of Art in 1904, when Roerich had been establishing himself as a specialist on Russian medievalism and folk art, on which he drew for his own primitivist canvasses of icons and traditional Slavic scenes. It was under Diaghilev’s direction that he had first achieved fame in the theatrical world with his backdrops for Alexander Borodin’s Prince Igor in 1909, where he had mixed pigment with egg yolk to create otherworldly scenes of brightly-coloured nomad tents under burning orange skies, in front of which the sword-wielding Tartar horsemen had danced. Audiences had been astonished at how, in the words of one critic, Roerich’s vision had given Parisians “the strange sensation of being transported to the ends of the earth”.

It was the creation of Rite of Spring that brought Roerich and Stravinsky together, but Roerich and Sergei Diaghilev had known each other for some years. Both had sat on the editorial board of the sumptuous avant-garde journal World of Art in 1904, when Roerich had been establishing himself as a specialist on Russian medievalism and folk art, on which he drew for his own primitivist canvasses of icons and traditional Slavic scenes. It was under Diaghilev’s direction that he had first achieved fame in the theatrical world with his backdrops for Alexander Borodin’s Prince Igor in 1909, where he had mixed pigment with egg yolk to create otherworldly scenes of brightly-coloured nomad tents under burning orange skies, in front of which the sword-wielding Tartar horsemen had danced. Audiences had been astonished at how, in the words of one critic, Roerich’s vision had given Parisians “the strange sensation of being transported to the ends of the earth”.

Nicholas Roerich was an intense and imposing man, with shaven head and pointed beard, whose turn of mind had since childhood tended to lead him backwards in time. The eldest son of a wealthy St. Petersburg lawyer, he had shown great aptitude in both arts and sciences, and while still in his teens had participated in several archaeological excavations of prehistoric Slavic tombs and burial mounds, unearthing swords, axes and bronze jewellery and meticulously reconstructing their ancient, pristine world in his mind’s eye. This world had found its way into his art: vivid canvasses combining primitive figures with sweeps of dazzling colour, above titles like ‘The Stone Age’, ‘Ritual Dance’ and ‘The Elders Gather’. The year before he met Stravinsky, he had conjured this world as the climax to a long essay on the origins of art, a scenario which would soon be realised in Rite of Spring:

Nicholas Roerich was an intense and imposing man, with shaven head and pointed beard, whose turn of mind had since childhood tended to lead him backwards in time. The eldest son of a wealthy St. Petersburg lawyer, he had shown great aptitude in both arts and sciences, and while still in his teens had participated in several archaeological excavations of prehistoric Slavic tombs and burial mounds, unearthing swords, axes and bronze jewellery and meticulously reconstructing their ancient, pristine world in his mind’s eye. This world had found its way into his art: vivid canvasses combining primitive figures with sweeps of dazzling colour, above titles like ‘The Stone Age’, ‘Ritual Dance’ and ‘The Elders Gather’. The year before he met Stravinsky, he had conjured this world as the climax to a long essay on the origins of art, a scenario which would soon be realised in Rite of Spring:

A lake. At the mouth of the river stands a row of houses. On the banks, dugout canoes and nets. The nets are woven long and fine. Hides are drying on the kilns: bear, wolf, lynx, vixen, beaver, sable, ermine…

A holiday. Let it be the one with which the victory of the springtime sun was always celebrated. When swift dances were danced, when all wished to please. When horns and pipes of bone and wood were played. The people rejoyced. Among them, art was born…

The meeting of Roerich and Stravinsky is a tangled tale, the various memoirs contradictory, but it seems likely they were introduced by Diaghilev. By some accounts, Roerich brought Stravinsky his idea for a Stone Age ballet, already titled The Great Sacrifice; by others, Stravinsky sought Roerich out to put flesh on the bones of his “fleeting vision of a dance of death and rebirth”. Most of their acquaintances reckoned that the idea was probably Roerich’s, or perhaps that the graphic, modernist motif of a dance to the death was Stravinsky’s, but that Roerich had provided its prehistoric setting. In any case, once introduced, the two collaborators plunged together into the ancient past to breathe life into what Stravinsky, in letters to Roerich, referred to as “our child”.

Over the summer of 1911, the pair decamped to Talashkino, the estate of Roerich’s patron, Princess Maria Tenisheva, where he was restoring her church with mosaics and icons using original medieval techniques. Talashkino was an artists’ colony, where students could learn traditional crafts and skills: woodcarving, embroidery, decorative techniques, murals, lacemaking. Together Roerich and Stravinsky studied the Princess’ collection of antique folk costumes, on which Roerich began to base the costumes for the ballet. Stravinsky was still searching for a voice: by his own account, his original vision was “not accompanied by concrete musical ideas”. In the meantime, Roerich was already briefing the press. “The new ballet”, he told the St. Petersburg Gazette, “will present a number of scenes from a ritualistic night in the time of the ancient Slavs…it will be the first to present a reincarnation of antiquity.”

Over the summer of 1911, the pair decamped to Talashkino, the estate of Roerich’s patron, Princess Maria Tenisheva, where he was restoring her church with mosaics and icons using original medieval techniques. Talashkino was an artists’ colony, where students could learn traditional crafts and skills: woodcarving, embroidery, decorative techniques, murals, lacemaking. Together Roerich and Stravinsky studied the Princess’ collection of antique folk costumes, on which Roerich began to base the costumes for the ballet. Stravinsky was still searching for a voice: by his own account, his original vision was “not accompanied by concrete musical ideas”. In the meantime, Roerich was already briefing the press. “The new ballet”, he told the St. Petersburg Gazette, “will present a number of scenes from a ritualistic night in the time of the ancient Slavs…it will be the first to present a reincarnation of antiquity.”

Roerich’s costumes and scene paintings, as they emerged, were works of exacting detail, conceived as authentic reconstructions and realised with traditional materials. The night of the Great Sacrifice was to be kupala, the Slavic midsummer festival which with the coming of Christianity had been converted into the Feast of St. John the Baptist, but which was thought in its original pagan form to have featured a huge bonfire and a giant flaming wheel which was rolled downhill, accompanied by dancing, singing and sacrificial rites. Roerich’s backdrops featured barren steppe-land under a vast oceanic sky, its flat plains punctuated by kurgans, the Scythian burial mounds he had excavated in his youth, their shape and proportions archaeologically exact. The costumes, crimson and white, were hand-dyed and stitched after Princess Tenisheva’a originals.

Roerich’s costumes and scene paintings, as they emerged, were works of exacting detail, conceived as authentic reconstructions and realised with traditional materials. The night of the Great Sacrifice was to be kupala, the Slavic midsummer festival which with the coming of Christianity had been converted into the Feast of St. John the Baptist, but which was thought in its original pagan form to have featured a huge bonfire and a giant flaming wheel which was rolled downhill, accompanied by dancing, singing and sacrificial rites. Roerich’s backdrops featured barren steppe-land under a vast oceanic sky, its flat plains punctuated by kurgans, the Scythian burial mounds he had excavated in his youth, their shape and proportions archaeologically exact. The costumes, crimson and white, were hand-dyed and stitched after Princess Tenisheva’a originals.

As rehearsals began, Roerich worked intimately with Vaslav Nijinsky on the challenge of a choreography which would, in Roerich’s words, “emulate the spirit of the prehistoric Slavs”. Nijinsky began developing ways of moving which he thought of as “prehistoric” – in his words, reconceiving “the roots of movement itself” – with results that seemed in some cases scarcely human. He found himself drawing heavily on Roerich’s visual world, imitating the hunched postures of the wooden idols in his paintings. “Roerich’s art”, he told his sister Bronislava, “inspires me as much as Stravinsky’s music”. Stravinsky, in a letter written in 1912, also acknowledged his debt to Roerich in the mounting of the production: “Who else could help me? Who else knows the secret of our ancestors’ close feeling for the earth?”

As rehearsals began, Roerich worked intimately with Vaslav Nijinsky on the challenge of a choreography which would, in Roerich’s words, “emulate the spirit of the prehistoric Slavs”. Nijinsky began developing ways of moving which he thought of as “prehistoric” – in his words, reconceiving “the roots of movement itself” – with results that seemed in some cases scarcely human. He found himself drawing heavily on Roerich’s visual world, imitating the hunched postures of the wooden idols in his paintings. “Roerich’s art”, he told his sister Bronislava, “inspires me as much as Stravinsky’s music”. Stravinsky, in a letter written in 1912, also acknowledged his debt to Roerich in the mounting of the production: “Who else could help me? Who else knows the secret of our ancestors’ close feeling for the earth?”

The ballet’s premiere in Paris, on 29 May 1913, has passed into legend. The protests began almost as soon as did the music, with its jarring time signatures and its deafening orchestra, including eight horns, and strings and woodwind screeching in their highest registers. By the time the outlandish spectacle of the dancing was added to the music, the audience was in uproar, some members directing insults at the performers and others shouting them down. The New York Times reviewer found his head being pummeled in time to the music by the person in the seat behind him: “my emotion was so great”, the critic recalled, “that I did not feel his blows for some time”. Fighting broke out, challenges to duel were served and accepted, and by the interval the police had been called in. Yet the chaos, like the scene to which it was responding, bore the imprint of Diaghilev’s coordinating hand. He had given away free tickets to boisterous students and avant-gardists, and their ostentatious applause of the ballet’s dissonant opening rhythms had played a large part in sparking the uproar. At dinner after the performance, he pronounced that “what took place was exactly what I wanted”. Roerich saw the scene rather differently. “Who knows”, he mused later, “perhaps at that moment they were inwardly exultant and expressing their feeling like the most primitive of peoples. But I must say, their wild primitivism had nothing in common with the refined primitivism of our ancestors”.

Although he continued to work sporadically for Diaghilev and others, Rite of Spring turned out to be the pinnacle of Roerich’s theatrical career. His high-minded approach to his art had always held him at arm’s length from the febrile and gossipy world of commercial collaboration, and from 1913 he became further distanced from it by the threat of war. While Nijinsky’s nervous breakdown at this time was steeped in apocalyptic terrors of eternal conflict, Roerich externalised his fears in paint: vast, gloomy canvases entitled ‘Conflagration’, ‘The Doomed City’ and one of his most highly acclaimed landscapes, ‘Battle in the Heavens’, where his familiar rolling steppe country is dominated and oppressed by a cloudscape of warring anvilheads.

Although he continued to work sporadically for Diaghilev and others, Rite of Spring turned out to be the pinnacle of Roerich’s theatrical career. His high-minded approach to his art had always held him at arm’s length from the febrile and gossipy world of commercial collaboration, and from 1913 he became further distanced from it by the threat of war. While Nijinsky’s nervous breakdown at this time was steeped in apocalyptic terrors of eternal conflict, Roerich externalised his fears in paint: vast, gloomy canvases entitled ‘Conflagration’, ‘The Doomed City’ and one of his most highly acclaimed landscapes, ‘Battle in the Heavens’, where his familiar rolling steppe country is dominated and oppressed by a cloudscape of warring anvilheads.

At the same time, though, he began to evolve a new style, light and optimistic in tone, its imagery drawn from the oriental dreamworld of the Bhagavad-gita and the Arabian Nights: waterfalls, lotus flowers, peacocks and temple priestesses posed with classical naivety in the shimmering light of rainbows and mountain dawns. Light though this work was, it concealed a serious intent: to conjure a parallel universe of peace. Roerich’s wife, Helena, whom he had married in 1900, was a fellow artist – a gifted musician – but also a devotee of Theosophy, widely read in eastern spiritualism; she would later translate Theosophy’s central text, Madame Blavatsky’s massive compendium The Secret Doctrine, into a million words of Russian. Although Roerich remained essentially a pantheist, co-opting countless different religious traditions into his own personal mythology, he now became increasingly drawn to the perennial philosophies of the East as the last possible saviours for a West which seemed bent on consuming itself in greed and destruction. He began to write prose poetry, evocations to the inner powers he was attempting to harness, meditations on war and peace that would evolve into a system he called Agni Yoga: a yoga of fire, one not of contemplation but of action:

At the same time, though, he began to evolve a new style, light and optimistic in tone, its imagery drawn from the oriental dreamworld of the Bhagavad-gita and the Arabian Nights: waterfalls, lotus flowers, peacocks and temple priestesses posed with classical naivety in the shimmering light of rainbows and mountain dawns. Light though this work was, it concealed a serious intent: to conjure a parallel universe of peace. Roerich’s wife, Helena, whom he had married in 1900, was a fellow artist – a gifted musician – but also a devotee of Theosophy, widely read in eastern spiritualism; she would later translate Theosophy’s central text, Madame Blavatsky’s massive compendium The Secret Doctrine, into a million words of Russian. Although Roerich remained essentially a pantheist, co-opting countless different religious traditions into his own personal mythology, he now became increasingly drawn to the perennial philosophies of the East as the last possible saviours for a West which seemed bent on consuming itself in greed and destruction. He began to write prose poetry, evocations to the inner powers he was attempting to harness, meditations on war and peace that would evolve into a system he called Agni Yoga: a yoga of fire, one not of contemplation but of action:

Life thunders – be watchful

Danger! The soul hearkens to its warning

The world is in turmoil – strive for salvation

In creation realise the happiness of life,

and unto the desert turn thine eye

Try to unfold the power of insight

That you may perceive the future unity of mankind

We possess the power to create and destroy obstacles

Thought is lightning

The spirit in revolt shatters the bolts of the prison

Straining to write and paint his way out of the fog of war, Roerich collapsed exhausted with pneumonia in 1915, and decided to leave Russia to recover. He may have wished to escape the revolution that was looming; those in the west claimed him as an escapee from Bolshevism, though Soviet tradition would claim him as one of their own, just as he would later be claimed as a prophet of the nascent Slavic nationalism. He himself continued to believe that art transcended politics, and his own alliegance was not to any warring faction but, increasingly, to a spiritual utopia. He left for Finland and then, after the war, for London, where he exhibited his art and was commissioned by Sir Thomas  Beecham to design his production of The Snow Maiden. In 1920 he accepted an invitation from the Chicago Art Institute to visit America, where he also exhibited in New York. He found some inspiration in the States, especially in the South-West, where he recognised many similarities between the Native Americans and his beloved prehistoric Slavs. He painted their adobe villages among the vibrant oranges and reds of the desert mesas, and worked a messianic tableau entitled ‘The Miracle’ into the foreground of the Grand Canyon.

Beecham to design his production of The Snow Maiden. In 1920 he accepted an invitation from the Chicago Art Institute to visit America, where he also exhibited in New York. He found some inspiration in the States, especially in the South-West, where he recognised many similarities between the Native Americans and his beloved prehistoric Slavs. He painted their adobe villages among the vibrant oranges and reds of the desert mesas, and worked a messianic tableau entitled ‘The Miracle’ into the foreground of the Grand Canyon.

But it was the East, not the West, that he yearned for, and in 1923 he and Helena, and their son George, now eighteen, embarked by boat to India. Arriving in Bombay, they set off on a tour of the sacred cultural sites – Agra, Elephanta Island, Varanasi – but soon found themselves drawn to the Himalayas, and particularly to the Buddhist legend of the lost city of Shambhala, long rumoured to lie hidden in a remote valley amongst the snow-capped ranges, home of the Maitreya, the future Buddha who will return to initiate a new cycle of existence.

Shambhala – soon to be popularised in the West as Shangri-la – was a legend with a venerable Eastern tradition, but the characteristically Western question as to whether or not it was a real place was a vexed one. Certainly it was described as such from ancient Buddhist texts onwards, but their assumption that the physical world was all maya, or illusion, implied that Shambhala itself might be best understood as a state of mind, a place of spiritual purity to be reached by meditation. The current Dalai Lama, when questioned on this precise point in 1981, replied archly that although it was “an actual land”, it was “not immediately approachable by ordinary persons, such as by buying an airplane ticket”. Yet within Theosophy, in which Shambhala had come to occupy a central role, Western devotees often pictured it as an elusive but concrete mountain fastness, inhabited by the Mahatmas or Hidden Masters who were guiding humanity on  its evolution. For the Roerichs, it seems to have been a symbol for peace, the last hope of humanity, but also for a level of enlightenment which could only be achieved by physical pilgrimage. In 1925 they mounted an ambitious expedition into the trackless wilds of the Himalayas and Central Asia, Roerich’s shaven head and now luxurious beard complemented by hunting jacket, boots, jodphurs and knee-length socks and, from time to time, a traditional Tartar longbow with which he had become adept. Just as Rite of Spring had been a project of radical modernism assembled from the textures of prehistory, so the quest for Shambhala seemed to Roerich to offer a future for humanity which could only be assembled from the timeless wisdom to be encountered at the roof of the world.

its evolution. For the Roerichs, it seems to have been a symbol for peace, the last hope of humanity, but also for a level of enlightenment which could only be achieved by physical pilgrimage. In 1925 they mounted an ambitious expedition into the trackless wilds of the Himalayas and Central Asia, Roerich’s shaven head and now luxurious beard complemented by hunting jacket, boots, jodphurs and knee-length socks and, from time to time, a traditional Tartar longbow with which he had become adept. Just as Rite of Spring had been a project of radical modernism assembled from the textures of prehistory, so the quest for Shambhala seemed to Roerich to offer a future for humanity which could only be assembled from the timeless wisdom to be encountered at the roof of the world.

As they trekked up through Kashmir into Ladakh and the high Himalayas, travelling with pilgrims and Tibetan lamas, Roerich and his family found themselves enveloped in a world of magic. Strange phenomena assailed them constantly, violet flames and glowing orbs of ball lightning dancing around their tents among the snows; and every group of pilgrims they passed had heard of Shambhala and its legends. The signs and portents multiplied, all pointing in the same direction:

Barren rocks, the endless desert. No travellers, no animals…

We look at one another, amazed, for we all sense simultaneously a strong perfume, as of the best incenses of India. Where does it come from? Are we not surrounded by barren rocks? The lama whispers: “Do you feel the fragrance of Shambhala?”

A sunny, unclouded morning – the blue sky is brilliant. Over our camp flies a huge, dark vulture. We and our Mongols watch it. Suddenly one of the Buryat lamas points to the sky. “What is that? A white balloon? An airplane?”

We notice something shiny, flying very high, from the northeast to the south. We bring three pairs of powerful field glasses from the tents and watch the huge spheroid body shining against the sun, clearly visible against the blue sky and moving very fast. Afterwards we see that it changes direction sharply from south to southwest and disappears behind the snow-peaked Humboldt chain. The whole camp follows the unusual apparition, and the lamas whisper: “The Sign of Shambhala!”

Many have subsequently co-opted this vision into a new mythology: the UFO sighting, to which it bears striking similarities, and which would not emerge for another thirty years. But Roerich also encountered more tangible mysteries, ones which led him not into the East and the future, but back to his own roots in the prehistoric European past:

On the rocks, halfway to Kashmir, some ancient carvings may be seen. In these ancient images one may distinguish ibexes with huge, powerfully curved horns, yaks, hunters, archers, round dances and ritual ceremonies…

We especially rejoyced at discovering typical menhirs and cromlechs in the Trans-Himalayan region of Tibet. You can imagine how remarkable it is to see the long rows of stones or the stone circles that vividly transport you to Carnac and the coast of Brittany… we also found ancient burial places in the Trans-Himalayas which recalled the Altai burial-places and the graves of the southern steppes.

On his quest for Shambhala, Roerich was astonished to find himself back in the world of Rite of Spring. Here, carved into the rock, was the khorovod, the circle dance of the ancient Slavs which he and Nijinsky had laboured so hard to reincarnate for the Paris stage. Was this its original form, predating even the primordial world of his imagination? He was itching to dig, and to establish the date of the carvings, but reluctantly noted that “excavations are not possible in Tibet, as the people claim that the Buddha prohibited touching the depths of the earth”. But the ancient roots of the images begged for interpretation, and their meaning struck him like a thunderbolt. Here, deep in the Himalayas, was the ancestral home of the people who eventually migrated west, becoming his own people: the Slavs, the Vikings, the Celts. The archaeological sites he had excavated in his youth, thousands of miles to the west, were not the beginning but the end of a tradition which had begun in the realm of Shambhala. “After their long journey”, he concluded, “the prehistoric druids recalled their ancient homes”.

The rock carvings Roerich had located were genuine, and are still genuinely mysterious. They are associated with a pre-Buddhist culture in the Himalayas which still survives among isolated pockets of people variously referred to as Dards, Drugpas and Minaro, who speak a language which is Indo-European, and has been demonstrated to represent a form of exceptional antiquity and purity. As late as the 1970s, the inhabitants of isolated valleys were still reported to be carving ibexes and hunting scenes on standing stones in a style identical to the rock art found at ancient Scythian sites. But archaeology in the region is still as problematic as it was for Roerich. Many of the carvings lie in the disputed and militarised northern borders between Pakistan and India, where travel permits are tightly controlled, and the majority of the sites stumbled on by Roerich and others still await excavation.

The rock carvings Roerich had located were genuine, and are still genuinely mysterious. They are associated with a pre-Buddhist culture in the Himalayas which still survives among isolated pockets of people variously referred to as Dards, Drugpas and Minaro, who speak a language which is Indo-European, and has been demonstrated to represent a form of exceptional antiquity and purity. As late as the 1970s, the inhabitants of isolated valleys were still reported to be carving ibexes and hunting scenes on standing stones in a style identical to the rock art found at ancient Scythian sites. But archaeology in the region is still as problematic as it was for Roerich. Many of the carvings lie in the disputed and militarised northern borders between Pakistan and India, where travel permits are tightly controlled, and the majority of the sites stumbled on by Roerich and others still await excavation.

The Roerichs’ quest, or pilgrimage, or research expedition, continued for three years, covering over fifteen thousand miles from the Himalayas to Mongolia, crossing a total of thirty-five mountain passes over fifteen thousand feet as well as the unmapped sand seas of the Taklamakan and Gobi deserts. Roerich kept journals throughout, mixing archaeological and ethnographic records with spiritual meditations and prose poems, but as ever his most eloquent expression of his state of mind was his art. He painted throughout, producing some of his finest work: dozens of crystalline Himalayan dawns and sunsets populated with deities, priests and temples, Buddhas and messiahs, goddeses and idols, shooting stars and mysterious lights, pilgrims huddled in mountain crevasses and yurt camps dwarfed by expanses of amber and cinnamon desert.

The Roerichs’ quest, or pilgrimage, or research expedition, continued for three years, covering over fifteen thousand miles from the Himalayas to Mongolia, crossing a total of thirty-five mountain passes over fifteen thousand feet as well as the unmapped sand seas of the Taklamakan and Gobi deserts. Roerich kept journals throughout, mixing archaeological and ethnographic records with spiritual meditations and prose poems, but as ever his most eloquent expression of his state of mind was his art. He painted throughout, producing some of his finest work: dozens of crystalline Himalayan dawns and sunsets populated with deities, priests and temples, Buddhas and messiahs, goddeses and idols, shooting stars and mysterious lights, pilgrims huddled in mountain crevasses and yurt camps dwarfed by expanses of amber and cinnamon desert.

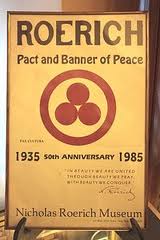

Descending finally from the Himalayas in 1928, the Roerichs settled in the lush Indian foothills of the Kullu Valley, setting up a Himalayan Research Institute to disseminate their findings and launching an international campaign for  world peace. Roerich continued to travel, mounting further expeditions to Manchuria and Inner Mongolia, and visiting the United States, where his admirers began to curate his prodigious output in a New York gallery, and his son George eventually became a professor at Harvard. Roerich travelled under the Banner of Peace, an ensign he had created – three red spheres arranged in a triangle on a white field, inspired both by the Red Cross and by his own spiritual symbolism: the trinity of art, science and religion. In 1935 he engineered the signing in the White House, in the presence of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, of the Roerich Pact, a treaty for the protection of artistic and scientific institutions and historical monuments which is still in force. He continued painting, campaigning for peace and working to preserve traditional Himalayan cultures until he died at his home in the Kullu Valley in 1947 while painting a final Himalayan mountainscape, in its foreground a white dove flying towards a meditating figure perched among the high peaks.

world peace. Roerich continued to travel, mounting further expeditions to Manchuria and Inner Mongolia, and visiting the United States, where his admirers began to curate his prodigious output in a New York gallery, and his son George eventually became a professor at Harvard. Roerich travelled under the Banner of Peace, an ensign he had created – three red spheres arranged in a triangle on a white field, inspired both by the Red Cross and by his own spiritual symbolism: the trinity of art, science and religion. In 1935 he engineered the signing in the White House, in the presence of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, of the Roerich Pact, a treaty for the protection of artistic and scientific institutions and historical monuments which is still in force. He continued painting, campaigning for peace and working to preserve traditional Himalayan cultures until he died at his home in the Kullu Valley in 1947 while painting a final Himalayan mountainscape, in its foreground a white dove flying towards a meditating figure perched among the high peaks.

Today, the exquisite Roerich Museum in New York houses the bulk of his art, but it is his house in Kullu, among scented pine forests and squat Shiva temples, that his presence can be most clearly felt. German, Russian and Tibetan disciples curate his shrine and spread his message through postcards and picture-books; the villa houses dozens of his paintings, his furniture, his car – a dusty 1930s Dodge with a huge brass hand-horn mounted on the side – and, in an outbuilding deep in the woods, his collection of traditional folk costumes of the Himalayas: woolen tunics and sheepskin boots, hand-stitched and embroidered, his homage to Princess Tenisheva’s collection which had inspired him to his own reincarnation of antiquity on the Paris stage.

Today, the exquisite Roerich Museum in New York houses the bulk of his art, but it is his house in Kullu, among scented pine forests and squat Shiva temples, that his presence can be most clearly felt. German, Russian and Tibetan disciples curate his shrine and spread his message through postcards and picture-books; the villa houses dozens of his paintings, his furniture, his car – a dusty 1930s Dodge with a huge brass hand-horn mounted on the side – and, in an outbuilding deep in the woods, his collection of traditional folk costumes of the Himalayas: woolen tunics and sheepskin boots, hand-stitched and embroidered, his homage to Princess Tenisheva’s collection which had inspired him to his own reincarnation of antiquity on the Paris stage.

This piece has previously appeared on www.nthposition.com

A shorter, spoken version was broadcast on BBC Radio 3 on 21 February, 2004