Bicycle Day Revisited

‘Kaleidoscopic, fantastic images burst in upon me, alternating, variegated, opening and then closing themselves in circles and spirals, exploding in coloured fountains’. The next morning, ‘the world was as if newly created’. So goes Albert Hofmann’s description of his pioneering LSD experience, on 19 April 1943 in Basel, Switzerland, during which he famously pedalled home from his laboratory on his bicycle.

Hofmann gave this classic account in his memoir LSD: My Problem Child, which recounts his journey from obscure Swiss biochemist to psychedelic celebrity. By the time of its publication in 1979, his first trip had become the founding moment of modern psychedelic culture. The image of the scientist on his bicycle, pedalling unsteadily into the technicolour future, has been printed on hundreds of thousands of acid blotters and is commemorated annually on 19 April, ‘Bicycle Day’, with parades, parties and day-glo cycle rides through cities around the globe. Beyond the psychedelic subculture, it’s become one of the best known ‘eureka moments’ in the history of science. Its 75th anniversary was recently commemorated in an exhibition at the National Library of Switzerland.

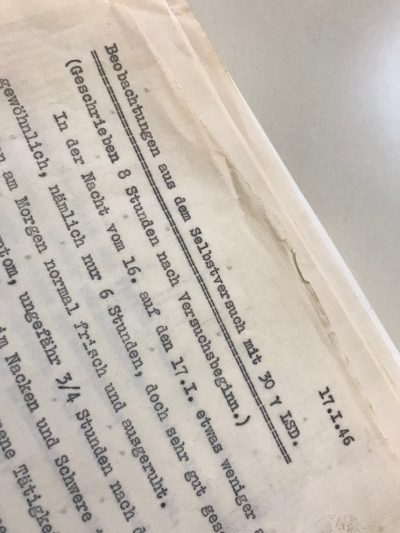

‘Eureka moments’ in science, however, have a tendency to compress a protracted process of discovery into a single image. Hofmann’s personal archive, which has now been acquired by Bern University, reveals a more complex story. It includes the original report on his first experiment that he filed three days later for his employers at the Sandoz pharmaceutical company, along with a series of further experiments that he undertook between 1943 and 1946 but never wrote about subsequently. The 1943 report is quite different from the celebrated version in LSD: My Problem Child. There are no fantastic images or coloured fountains. It’s a gruelling episode that Hofmann experienced as an acute poisoning, with symptoms that were mostly physical and extremely unpleasant. Rather than a psychedelic, he and the visiting doctor compared them to a massive overdose of amphetamines.

To begin with, the two versions run along similar lines: in fact, Hofmann’s 1979 memoir introduces the episode with a quote from the report he wrote on 22 April 1943 to his boss, Professor Arthur Stoll, director of the pharmaceutical department at Sandoz. In this four-page document, Hofmann begins the story three days earlier, on 16 April, when he became dizzy while working in the lab and went home to lie down in a darkened room, at which point he ‘sank into a not unpleasant, intoxicated-like condition, characterised by an extremely stimulated imagination’. ‘The nature and course of this disorder made me suspect it was a toxic effect’, the original report continued. Three days later he decided to make a self-experiment with the substance he believed to be responsible: d-lysergic acid diethylamine tartrate, or LSD.

On the morning of 19 April he synthesised 0.5ml of the compound, dissolved it in 10cc of water, and at 4.20pm took 250µg, 0.000025 of a gram, the smallest dose he thought he might conceivably notice.  At 5pm he began to feel dizzy, as he had previously, and decided to cycle home. On the bike ride, the symptoms became stronger: ‘I had great difficulty in speaking clearly and my field of vision fluctuated and swam like an image in a distorted mirror’, he wrote at the time, very much as he described it in his 1979 memoir. He ‘had the feeling that I was not moving from the spot, although my colleague said I was moving at a fast pace’. When he arrived home he called on his neighbour, who summoned the nearest doctor.

At 5pm he began to feel dizzy, as he had previously, and decided to cycle home. On the bike ride, the symptoms became stronger: ‘I had great difficulty in speaking clearly and my field of vision fluctuated and swam like an image in a distorted mirror’, he wrote at the time, very much as he described it in his 1979 memoir. He ‘had the feeling that I was not moving from the spot, although my colleague said I was moving at a fast pace’. When he arrived home he called on his neighbour, who summoned the nearest doctor.

The symptoms soon became overwhelming. Hofmann recorded them at the time as ‘dizziness, visual disturbance, the faces of those present seemed vividly coloured and grimacing; powerful motor disturbances, alternating with paralysis; my head, body and limbs all felt heavy, as if filled with metal; cramps in the calves, hands cold and without sensation; a metallic taste on the tongue; dry and constricted throat; a feeling of suffocation; confusion alternating with clear recognition of my situation, in which I felt outside myself as a neutral observer as I half-crazily cried or muttered indistinctly’. Given that Hofmann had taken a full-trigger dose of LSD with no idea what it was going to do, it’s not surprising that he thought he was going crazy or dying.

By the time the doctor, Walter Schilling, arrived, ‘the peak of the crisis was already past’. Schilling’s notes, preserved in the archive, record that he was struck by Hofmann’s ‘motor disturbances and anxious mood’ but that he could find nothing seriously wrong with him. ‘Objectively his heart action was regular…his pulse was average, his breathing calm and deep.’

It’s here that Hofmann’s later memoir parts company with the report he wrote at the time. ‘Now, little by little’, he wrote later, ‘I could begin to enjoy the unprecedented colours and plays of shapes that persisted behind my closed eyes’. Then come the kaleidoscopes and coloured fountains. But there’s little of this in the original report, which mentions ‘sensory distortions’ but describes the visions as ‘unpleasant, predominantly toxic-green and blue tones’. The 1943 document concludes with Hofmann’s suggestion, which he discussed with Dr. Schilling at the time, that the ‘symptoms were very similar to those that might be might be observed in an overdose of an amphetamine-type stimulant such as Pervitin’ (a German brand of methamphetamine that had been widely available during the 1930s).

The next morning, Hofmann wrote in 1979, ‘a sensation of well-being and renewed life suffused me…The world was as if newly created’. But his report at the time simply states that he woke ‘feeling perfectly healthy again, if somewhat weary, but remained all day in bed on the advice of the physician’.

*

The first acid trip had been a shattering experience, but Hofmann knew he was on to something remarkable. He could think of no other substance that produced such a powerful effect from such a tiny dose. ‘The toxic dose of Pervitin is somewhere in the high tenths of a gram’, he wrote, which would make LSD around 1000 times stronger. During the course of 1943 he took it three more times, though at much lower doses (he never again took anything like the 250µg of his first trip, which he regarded for the rest of his life as a massive overdose).  On 30 December he submitted a report on these experiments to Arthur Stoll, which has never been reprinted or translated into English.

On 30 December he submitted a report on these experiments to Arthur Stoll, which has never been reprinted or translated into English.

Switzerland was an island of neutrality during the war, but Basel was a border city and Hofmann was at this time doing military service. He was posted in Claro, in the Swiss canton of Ticino, among the forested mountains near the frontier with Mussolini’s Italy. On 29 September he took a small dose of 20µg at his barracks, after which he drank coffee and grappa with his fellow soldiers and played table football and billiards. As the effects came on, he ‘withdrew almost completely into myself, my own thoughts’, and went to bed with images playing across his closed eyes and ‘warm comfortable feelings’.

For the second experiment, on 2 October, he took his 20µg later in the evening, just before going to bed. This time the experience was much less pleasant. ‘I had disturbing dreams’, he recorded, including ‘a crazy mutilated woman with her arms cut off and burned out eyes. My companions thought I was insane and I was unable to convince them that I wasn’t’. On Hallowe’en he ventured a larger dose of 30µg, which he took after a post-lunch nap (he was off duty, as it was a Sunday). He felt a ‘slight daze, shivers, nausea, a faint metallic taste in my mouth’ and returned to bed, feeling the need to lie still, along with some ‘stimulation in the genital region’. He entered ‘a dozy state’, in which ‘disturbing, uncanny phantasms, partly sensual visions’ flitted through his mind. At 10pm he got up for a biscuit and some chocolate.

The following year, 1944, Sandoz began testing LSD on animals and Hofmann synthesised a couple of variants, which he designated ‘dihydro-LSD’ and ‘d-Iso-LSD’. They were sampled by some of his colleagues, including his assistant Susi Ramstein, but they proved less psychoactive than the original. On 17 January 1946 Hofmann reported another self-experiment with LSD, in which he relaxed into the experience much more than he had on previous occasions. Sitting at home in his armchair after a dose of 30µg he ‘was struck by the beautiful colours of the tabletop…wonderful warm tones that changed from orange to blood-red to purple’ as the electric lamp brightened and dimmed. He had ‘great fun with Rorschach images’, the inkblot personality-test cards, spending around half an hour absorbed in studying their abstract shapes. He was finally enjoying some well-earned quality time with his problem child.

*

But the first truly psychedelic description of an acid trip would appear the following year, from another source. LSD had begun to circulate among the pharmacists at Sandoz, including Hofmann’s director Arthur Stoll, who sought the opinion of his son Werner, a psychiatrist at the Burghölzli clinic in Zurich. Werner Stoll took 60µg, only a quarter of the dose that had steamrollered Hofmann on Bicycle Day but twice as much as his subsequent experiments. It turned out to be just right. Lying in a darkened room, Stoll was mesmerised by dazzling, dancing abstract shapes and patterns: ‘a profusion of circles, vortices, sparks, showers, crosses and spirals in constant, racing flux’. Gradually, ‘more highly organised visions also appeared: arches, rows of arches, a sea of roofs, desert landscapes, terraces, flickering fire, starry skies of unbelievable splendour’. His state of mind was ‘consciously euphoric. I enjoyed the condition’, and ‘knew the euphoria and exultation of an artistic vision’. In conclusion, he wrote: ‘Terms such as ‘fireworks’ or ‘kaleidoscopic’ were poor and inadequate’.

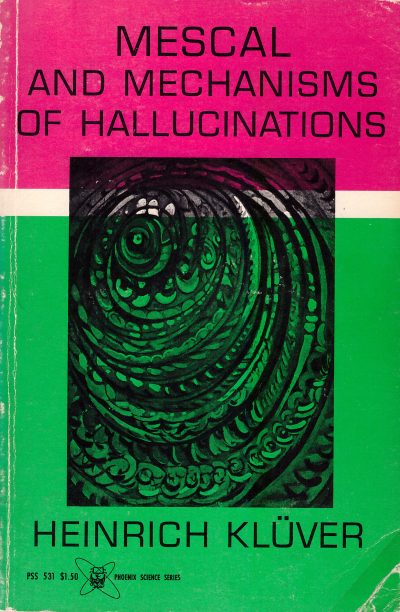

Werner Stoll’s report, published in 1947 in a Swiss psychiatry journal, was titled ‘Lysergic acid diethylamide, a phantasticum from the ergot group’. Hofmann had theorised that LSD was an amphetamine-type stimulant, but Stoll reached for a different category: ‘phantasticum’ was a term coined back in the 1920s by the pharmacist Louis Lewin to describe vision-producing drugs such as cannabis, datura, ayahuasca, fly agaric – and particularly mescaline, which had been isolated from the peyote cactus in 1897 and first synthesised in the laboratory in 1919.

During the 1920s mescaline was investigated thoroughly by German psychologists. Researchers such as Kurt Beringer and Heinrich Klüver published book-length studies on it, focusing particularly on its closed-eye visual hallucinations.  They tracked the way that these progressed from abstract shapes – spirals, lattices, tunnels – to recognisable objects, just as Werner Stoll now did. From this point, mescaline became the model to which the newly discovered LSD was compared. As Hofmann later wrote in his memoir, ‘the picture of the activity of LSD derived from these first investigations was not new. It largely matched the commonly held view of mescaline’. The main difference was in the dose: a gram of mescaline was three or four doses, a gram of LSD was several thousand. But the visual language of the acid trip, as it emerged, drew on templates that had been set down a generation earlier.

They tracked the way that these progressed from abstract shapes – spirals, lattices, tunnels – to recognisable objects, just as Werner Stoll now did. From this point, mescaline became the model to which the newly discovered LSD was compared. As Hofmann later wrote in his memoir, ‘the picture of the activity of LSD derived from these first investigations was not new. It largely matched the commonly held view of mescaline’. The main difference was in the dose: a gram of mescaline was three or four doses, a gram of LSD was several thousand. But the visual language of the acid trip, as it emerged, drew on templates that had been set down a generation earlier.

The Bicycle Day celebrations that mark every 19 April would have been incomprehensible to Hofmann in 1943. The idea that LSD could be a source of personal revelation or spiritual transcendence was still far in the future. Acid was at the start of its own long strange trip: from research chemical to psychiatric wonder drug, brainwashing tool to agent of ego-dissolution, cosmic insight and cultural revolution. As Hoffman wrote in 1979, ‘the last thing I could have anticipated was that this substance should ever come to be used as anything like a pleasure drug’.

As the psychedelic counterculture emerged, its origin story crystallised into a vivid and irresistible eureka moment: strait-laced scientist has mindblowing cosmic epiphany on his bicycle. But the modern psychedelic era didn’t emerge fully formed with the first acid trip, any more than Isaac Newton conceived his theory of gravity in an instant when an apple fell on his head. On 19 April 1943 Hofmann’s thoughts were running along entirely different lines. Was this a stimulant or a deliriant poison? Had he taken a massive, possibly fatal overdose? The fireworks, kaleidoscopes and coloured fountains, and the new world that dawned in their afterglow, would take a little longer to come into focus.

A version of this article appeared in VICE US in December 2018

Albert Hofmann’s self-experimental reports 1943-6 are held as ‘Hofmann 148.1’ in the Instituts für Medizingeschichte der Universität Bern (IMG).