Edward and Catherine Despard

In the late summer of 1790, when Colonel Edward Marcus Despard arrived in London after nearly twenty years of British military service in the Caribbean, he brought with him his wife, Catherine, and their young son, James. Catherine was a black woman, and their mixed race marriage was highly unusual in Britain at the time. They lived together as man and wife in London, and Catherine took on an increasingly public role in defending her husband against charges of terrorism and sedition. She lobbied and campaigned on his behalf, taking the fight to the highest authorities in government and the judiciary, until Despard’s dramatic execution on charges of high treason in 1803.

There were various rumours about Catherine’s background: by some accounts she was the daughter of a Jamaican preacher, by others she was an educated Spanish creole. Recently uncovered parish records show that her mother was a free black woman of the parish of St. Andrews outside Kingston, Jamaica. Despard may have met her there, perhaps in 1784 or 1785 while he was patrolling the waters between Jamaica and the Mosquito Shore of Central America in preparation for establishing a new British settlement. She may have been responsible for nursing him through one of his many tropical illnesses, as Cuba Cornwallis had done for Despard’s comrade-in-arms, Horatio Nelson. But whatever stories were attached to her it is clear that, in London, she confounded the expectations and prejudices of all who met her.

Despard had been recalled from the Caribbean to London to settle an administrative dispute, which had turned on the question of the equal treatment of races.  After a series of heroic military engagements against the Spanish, he was given charge of the newly ceded British enclave of the Bay of Honduras, present-day Belize. As part of the treaty that granted the new enclave, British settlers up and down the Mosquito Shore were required to resettle in the Bay of Honduras, and Despard was charged with accommodating them. Some were wealthy planters of Anglo-Saxon origin, but the majority were a ‘motley crew’ of labourers, brewers, smugglers, freed slaves and ex-military volunteers who had been living in straggling and remote communities up and down the coast and were known collectively as the Shoremen.

After a series of heroic military engagements against the Spanish, he was given charge of the newly ceded British enclave of the Bay of Honduras, present-day Belize. As part of the treaty that granted the new enclave, British settlers up and down the Mosquito Shore were required to resettle in the Bay of Honduras, and Despard was charged with accommodating them. Some were wealthy planters of Anglo-Saxon origin, but the majority were a ‘motley crew’ of labourers, brewers, smugglers, freed slaves and ex-military volunteers who had been living in straggling and remote communities up and down the coast and were known collectively as the Shoremen.

Despard was instructed by the Home Secretary, Lord Sydney, to accommodate the Shoremen in the new enclave ‘in preference to all other persons whatsoever’. He offered them parcels of land on which to build houses and grow crops for their subsistence, and he did so without distinction of colour, distributing lots on an equal basis to mulattos, blacks and whites. This policy was fiercely opposed by the small number of long-term white settlers in the Bay who had become wealthy through exporting mahogany to Britain, where it provided the materials for furniture makers such as Thomas Chippendale. These Baymen, as they were known, had previously divided the Bay territory informally among themselves, even though it was technically owned by the Spanish crown.

The terms of the new treaty superseded these old arrangements, but the Baymen protested vigorously. They insisted to Lord Sydney that the rights of ‘people of mixed colour and negroes’ should be subservient to those of the established Anglo-Saxon colonists. Despard replied to Sydney, that the decision ‘must be governed by the laws of England, which knows no such distinction’. Technically, he was quite correct: there was no colour bar in English law, and the Baymen were, in his phrase, a ‘very arbitrary aristocracy’ who were attempting to monopolise the new settlement’s wealth.  But the Baymen kept up their protests and succeeded in persuading a new Home Secretary, William Wyndham Grenville, that Despard’s actions are threatening the Bay’s profitable mahogany trade. Grenville suspended Despard from his post, pending an enquiry. His response was to stand for re-election as magistrate in the local polls, where he won a landslide majority. The Baymen protested once more that his mandate had only been secured by the inclusion on the register of ‘ignorant turtlers and people of colour’ who had never previously voted in magistracy elections. In 1790, Despard was forced to return to London to argue his case.

But the Baymen kept up their protests and succeeded in persuading a new Home Secretary, William Wyndham Grenville, that Despard’s actions are threatening the Bay’s profitable mahogany trade. Grenville suspended Despard from his post, pending an enquiry. His response was to stand for re-election as magistrate in the local polls, where he won a landslide majority. The Baymen protested once more that his mandate had only been secured by the inclusion on the register of ‘ignorant turtlers and people of colour’ who had never previously voted in magistracy elections. In 1790, Despard was forced to return to London to argue his case.

The exchanges between Despard, the Baymen and the Home Office were detailed and protracted, and the debate was later picked over in public when Despard was interned by the government as a suspected terrorist. Yet the fact of his marriage to Catherine, and of her ethnicity, was never mentioned in connection with it. The Baymen, although they made much of Despard’s partiality to ‘people of colour’, made no reference to his wife and child. James Bannantine, Despard’s secretary in the Bay, published a vigorous defence of his former employer’s actions, yet he too found no room to mention Catherine. She is absent, too, from contemporary histories of black people in Britain, which around 1790 record servants, page boys, scholars, war veterans, bare-knuckle boxers, abolitionists, freed slaves and prostitutes, but no black woman married to a British gentleman. The Despards, in ways of which they both seem to have been partly unaware, had formed a union that was unprecedented, and on which nobody wished to be the first to pronounce judgement.

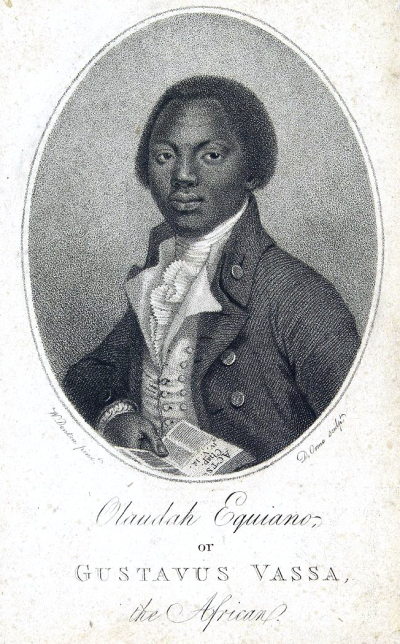

There was no explicit legal or moral reason why Despard and Catherine should not have married, nor why they should not have returned to London together. It was well known that British officers and gentlemen in the colonies frequently had mistresses of colour, and in many cases produced children of mixed race.  Indeed, the virtue of openly mixed race marriages was, at the moment of the Despards’ arrival in London, being championed by the former slave Olaudah Equiano, who was touring England promoting his powerful and finely-written autobiography The Interesting Narrative. ‘Why not establish intermarriage at home, and in our colonies?’, Equiano asked. ‘And encourage open, free and generous love, upon Nature’s own wide and extensive plan, subservient only to moral rectitude, without distinction of the colour of a skin?’

Indeed, the virtue of openly mixed race marriages was, at the moment of the Despards’ arrival in London, being championed by the former slave Olaudah Equiano, who was touring England promoting his powerful and finely-written autobiography The Interesting Narrative. ‘Why not establish intermarriage at home, and in our colonies?’, Equiano asked. ‘And encourage open, free and generous love, upon Nature’s own wide and extensive plan, subservient only to moral rectitude, without distinction of the colour of a skin?’

This was an appeal that was heard with generosity in the literary clubs, Wesleyan churches and abolitionist meetings where Equiano spoke. It may be that the Baymen had made no reference to Catherine in their despatches to the Home Office because they were aware that the ideals of of racial equality and the abolition of slavery, a practice on which their trade depended, held a claim to the moral high ground back in Britain. To criticize the Despards on the basis of their mixed race marriage ran the risk of damaging the accuser more than the accused.

Yet it was precisely the debate in which the Despards were engaged – the question of who was to count as British in an expanding colonial world – that would generate the scientific racism that entrenched itself in the century to come. In the next generation of Despards, Edward and Catherine’s marriage would be denied: Victorian family memoirs would refer to Catherine as his ‘black housekeeper’, and ‘the poor woman who called herself his wife’. James would be ascribed to a previous lover, and both would be written out of the family tree.

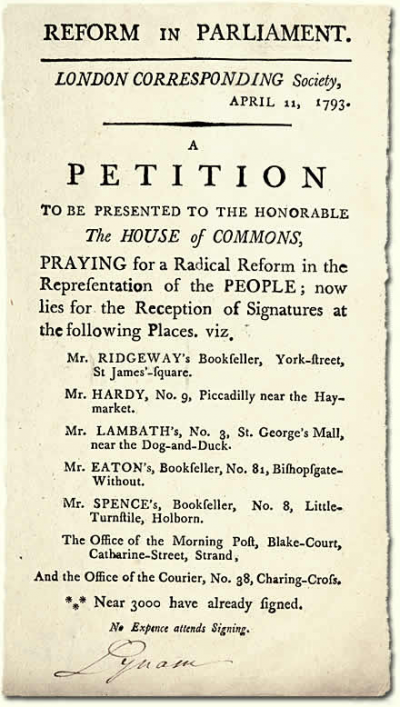

The Despards intended their visit to London to be brief, but attempting to right the wrongs of the Bay colony was to consume the rest of their life together. Despard’s case was viewed with little sympathy by a Home Office committed to supporting the wealthy planters in the colonies and little interested in refereeing disputes over local justice. He was not offered a new commission, and he was pursued by writs from the Baymen’s trading partners which, though eventually dismissed by the courts, bankrupted him and sent him to debtors’ prison for two years. During this period, he read Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man, which gave eloquent voice to his own conviction that popular electoral mandates should be the basis of government.  When he left prison he committed himself to the campaign for political reform. He joined the London Corresponding Society, an association recently established by and largely composed of artisans and working men, among whom he was a conspicuous gentleman member. His Anglo-Irish origins gave him a particular interest in the cause of Irish independence, and he also joined the United Irishmen, an organisation with similar aims established in Dublin in 1791 by the Protestant lawyer Wolfe Tone.

When he left prison he committed himself to the campaign for political reform. He joined the London Corresponding Society, an association recently established by and largely composed of artisans and working men, among whom he was a conspicuous gentleman member. His Anglo-Irish origins gave him a particular interest in the cause of Irish independence, and he also joined the United Irishmen, an organisation with similar aims established in Dublin in 1791 by the Protestant lawyer Wolfe Tone.

With Britain at war with revolutionary France, these campaigns for political reform were a cause of acute anxiety to the government, and new laws were passed to make it easier to prosecute political dissidents for sedition and treason. Despard was placed under surveillance by espionage rings coordinated by the Home Office and the Bow Street magistrates. Their testimony is unreliable on many points, but they claim that during this period he associated with known revolutionaries and terrorists and was involved in plots with the Irish rebel militias, and perhaps with the French enemy. According to these reports, the Despards moved lodgings every few months: Soho, St. George’s Fields, Berkeley Square. The also suggest that Catherine was worried about the political risks her husband was taking and he began to use a safe house in Camden Town for meetings without her knowledge.

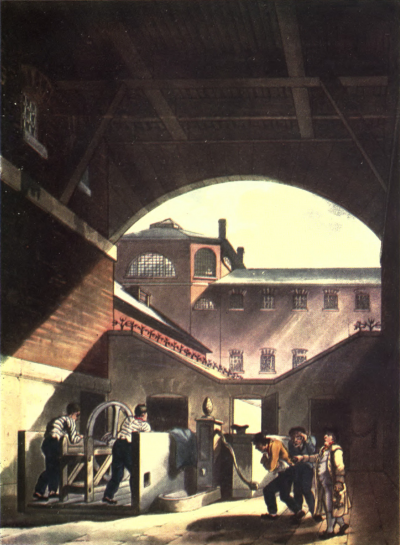

The government swooped on the London Corresponding Society and the United Irish in 1798 after a group of suspects was arrested at Margate, one of whom was found to be carrying plans for an Irish republican uprising to the French directory. Despard was arrested at lodgings in Meard Street, Soho, where the Times reported that he had been found in bed with ‘a black woman’. Along with around thirty others, he was held in Coldbath Fields, a recently constructed high security prison in Clerkenwell.  When the Great Rebellion broke in Ireland a few months later, the government suspended the right of habeas corpus, and Despard and his fellow suspects found themselves confined indefinitely without trial.

When the Great Rebellion broke in Ireland a few months later, the government suspended the right of habeas corpus, and Despard and his fellow suspects found themselves confined indefinitely without trial.

Catherine began a campaign to agitate for Despard’s release. She enlisted the help of the independent MP Sir Francis Burdett, who raised the question of the Coldbath Fields detainees in the House of Commons. A letter by Catherine was read in the course of the debate, in which she reported that her husband was being held ‘without either fire or candle, table, knife, fork, a glazed window or even a book to read’. The government minister George Canning implied that Catherine was being used as a mouthpiece by political subversives, claiming that ‘it was a well-written letter, and the fair sex would pardon him, if he said it was a little beyond their style in general’. Catherine’s blackness was as invisible as ever; her gender was enough to make her eloquent appeal suspicious. Burdett replied that Catherine ‘is not so illiterate as Mr.Canning would have us believe’, to which the Attorney General, Sir John Scott, replied with the threat that ‘there were some wives who had met with much indulgence, in not being taken up and confined as well as their husbands’.

Despard was held for three years before the suspension of habeas corpus lapsed and he was freed, in theory at least without a stain on his character. Within a year he was arrested once more, in the Oakley Arms, a Lambeth pub, in the company of a number of disaffected soldiers suspected of plotting a mutiny. This time he was charged with high treason: an alleged conspiracy to assassinate King George III and spark a republican revolution. Despard pled not guilty but was convicted on the evidence of government informers.  He was sentenced to be publicly hung, drawn and quartered, a sentence that had barely been handed down in living memory.

He was sentenced to be publicly hung, drawn and quartered, a sentence that had barely been handed down in living memory.

Catherine persisted with her campaign on his behalf. She approached Lord Nelson, who had appeared as a character witness at Despard’s trial, to plead with the Prime Minister for leniency; together, the Despards spent their time in prison together writing a petition to the King. Either as a result of these appeals, or fear of public unrest, the public dismemberment and disembowelling were waived, but Despard was still to be hung and beheaded. Catherine had been hoping for a pardon, or a commutation of the sentence; the Observer reported that she ‘had almost sunk under the anticipated horror of his fate; her feelings, when the dreadful order arrived, can scarcely be conceived – we cannot pretend to describe them’. She was allowed a final meeting with her husband during which, according to reports, ‘the Colonel betrayed nothing like an unbecoming weakness’.

Catherine’s final service to her husband was to insist on his hereditary right to be buried in St. Paul’s cathedral, a campaign she won despite protests to the government from the Lord Mayor of London. After his death she was supported by a pension from Sir Francis Burdett, and may have spent time in Ireland, before dying in Somers Town, London, in 1815. Their son James joined the French army but returned to Britain after the Napoleonic Wars. The final trace of him in the family records is an episode recounted by General John Despard, Edward’s older brother, who was leaving a London theatre when he heard a carriage driver calling the family name. He made his way towards the carriage he assumed was his, ‘and there appeared a flashy Creole and a flashy young lady on his arm, and they both stepped into it.’ After this brief glimpse, James – and any future black Despards – melted into the night streets of London.

—

A shorter version of this piece is included in The Oxford Companion to Black British History (2006)

Related book: The Unfortunate Colonel Despard