The Acid Farmers

History has remembered LSD as the creation of one man, Albert Hofmann, the Sandoz chemist who first synthesised it in 1938 and who took the world’s first acid trip in 1943. In his 1979 memoir, LSD: My Problem Child, Hofmann wrote that ‘the investigations on ergot alkaloids’ that led to the discovery of LSD ‘were conducted by myself alone’. But his laboratory work was only a small part of a large-scale, company-wide operation. Research into ergot, the toxic fungus from which LSD was synthesised, had begun many years before Hofmann joined the company. By the time of his first trip Sandoz had embarked on an experimental programme for large-scale ergot cultivation, and during the 1950s they developed new techniques and machinery to ramp its production up to industrial levels, feeding the fast-growing global demand for LSD.

The ergot project had originally been the brainchild of Hofmann’s boss, Arthur Stoll, the director of pharmaceutical research at Sandoz, who had isolated the first alkaloid drugs from it back in 1921. Stoll had been attracted to it by its long and fascinating history: familiar since medieval times both as a deadly poison and a folk medicine.

Ergot (Claviceps purpurea) is a fungus that grows as a parasite on rye, coating its seedheads with a black crust, or sclerotium.  Bread made from infected rye gave rise to epidemics of the disease traditionally known as St. Anthony’s Fire and later described by doctors as ‘ergotism’. Its terrifying array of symptoms includes seizures, skin lesions, psychotic disturbances and a ‘dry gangrene’ that can cause fingers or toes to lose sensation and rot away. This last symptom is a response to its vasoconstrictive properties, which tighten arteries and stop blood flow. This was the basis for the use of ergot sclerotium in early medicine, especially obstetrics: it produces uterine contractions, and was used to speed up childbirth or trigger abortions. In German this gave it the common name Mutterkorn, ‘mother’s corn’.

Bread made from infected rye gave rise to epidemics of the disease traditionally known as St. Anthony’s Fire and later described by doctors as ‘ergotism’. Its terrifying array of symptoms includes seizures, skin lesions, psychotic disturbances and a ‘dry gangrene’ that can cause fingers or toes to lose sensation and rot away. This last symptom is a response to its vasoconstrictive properties, which tighten arteries and stop blood flow. This was the basis for the use of ergot sclerotium in early medicine, especially obstetrics: it produces uterine contractions, and was used to speed up childbirth or trigger abortions. In German this gave it the common name Mutterkorn, ‘mother’s corn’.

Stoll studied the history of ergot and wrote a book about it. In 1936 he assigned Albert Hofmann to investigate its chemistry at the Sandoz labs. The indole alkaloids it contained, including the vasoconstrictor ergotamine which Stoll had isolated many years previously, were all based on lysergic acid: an unstable compound which Hofmann was tasked with turning into medically useful forms.

At this point ergot was a scarce and expensive commodity. Rye farmers had typically regarded it as a blight that ruined their crop, and had always done their best to suppress its growth. Small amounts were produced agriculturally in the Emmenthal valley in mid-Switzerland, where it flourished in the relatively humid climate. Its use in the Sandoz laboratories was tightly controlled. Hofmann remembers Stoll admonishing him for ordering even as little as half a gram: ‘I needed to adopt microchemical procedures if I was to work with his costly substances’. When Hofmann first synthesised LSD in 1938, a small quantity was expended on animal testing, which demonstrated no particular vasoconstricting properties. After that it was on to the next compound.

By the time of Hofmann’s famous trip in 1943, the situation had changed. During the war, Sandoz began to systematise production of lysergic acid with new agricultural techniques. ‘They grew 5000 rye plants and selected the five most promising strains’, says Beat Bächi of Bern University, who has been studying the Hofmann and Sandoz archives for his forthcoming book on Sandoz, ergot and LSD. They cultured and selected the most productive spores of the ergot fungus, and supplied their specially bred strains to the Emmenthal’s rye farmers. ‘Sandoz kept extremely tight control of the operation’, according to Bächi. Long before the modern era of genetic patents, farmers were obliged to sign contacts prohibiting them from using the Sandoz-bred rye and ergot for their own purposes, or keeping the seeds and spores.

The ergot cultivation programme was a success. Photos from the Sandoz archives show experimental fields of rye divided into two, one half growing normally, the other black with masses of ergot sclerotia. In 1947 the psychiatrist Werner Stoll, Arthur’s son, made a series of self-experiments with LSD in which he experienced euphoria and vivid hallucinations. He recommended it for further clinical research as a psychiatric medicine.

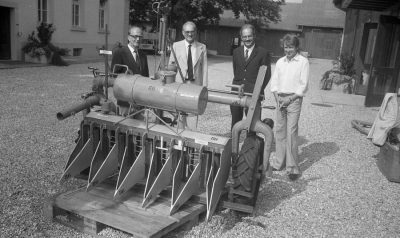

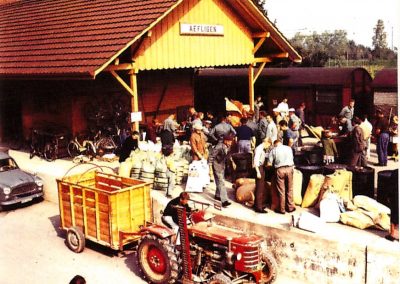

By now Sandoz was gearing up for large-scale production. Working together with the machinery engineers Bucher Guyer, they designed a multi-needle gun to inoculate rye heads with ergot spores, and a special tractor to harvest the heads. The project was conducted with government approval under wartime protocols of secrecy. Photos in the Sandoz archives show the ergot farmers gathered on the platform of the local train station with their crop: large sacks of sclerotia-covered grain ready for shipment to Basel and the Sandoz laboratories.

Delysid, the brand name for LSD, was only one of the Sandoz products for which the ergot was destined. There was also Methergine, a drug developed for ergot’s traditional use of slowing bleeding during childbirth, and Hydergine, a medication for improving circulation and brain function in the elderly that became a bestseller. But as more psychiatrists and Sandoz pharmacists experimented with LSD, they became convinced that it could play an important role in brain research and the treatment of mental illness. ‘They were hugely excited by its potential’, according to Magaly Tornay, who worked in the Sandoz LSD archives for her 2016 book Zugriffe auf das Ich (Concepts of the Self). ‘By the late 1950s they were predicting that, with LSD, the cypher of the mind would be broken within five years’. Even with the new agricultural production, they struggled to grow enough ergot to meet the demand. ‘There are letters requesting lysergic acid from Italy, and asking other pharma companies like Eli Lilly whether they had any stocks to spare’.

Delysid remained a research chemical rather than a fully developed product. Sandoz were unsure of the doses and applications they should recommend for it, and supplied samples free to psychiatrists in return for feedback on how it was being used. By the early 1960s this freewheeling strategy was getting harder to sustain. In the USA, new Federal Drug Administration (FDA) rules meant that drugs had to be submitted to stringent testing before human trials were permitted, and their intended use needed to be specified in advance. At the same time, the growing interest in LSD as a tool for consciousness expansion undermined attempts to establish it as a pharmaceutical drug. During the 1950s LSD had been valuable to Sandoz in building their global reputation, but as the 1960s progressed it became a PR problem. They no longer wanted to be so closely identified with a drug that was now hitting the headlines for all the wrong reasons.

Delysid remained a research chemical rather than a fully developed product. Sandoz were unsure of the doses and applications they should recommend for it, and supplied samples free to psychiatrists in return for feedback on how it was being used. By the early 1960s this freewheeling strategy was getting harder to sustain. In the USA, new Federal Drug Administration (FDA) rules meant that drugs had to be submitted to stringent testing before human trials were permitted, and their intended use needed to be specified in advance. At the same time, the growing interest in LSD as a tool for consciousness expansion undermined attempts to establish it as a pharmaceutical drug. During the 1950s LSD had been valuable to Sandoz in building their global reputation, but as the 1960s progressed it became a PR problem. They no longer wanted to be so closely identified with a drug that was now hitting the headlines for all the wrong reasons.

The final straw came in January 1963 when Timothy Leary, after being dismissed from Harvard University, ordered 500g of Delysid from Sandoz: enough for several million doses. Sandoz contacted the FDA for approval, but a licence wasn’t granted and they refused to supply the order. The same year their patent on LSD expired. In 1965 Sandoz officially stopped production and distribution, with a statement that LSD had ‘in some parts of the world’ become ‘a serious threat to public health’. But the ergot farmers of the Emmenthal had by now seeded acid around the globe. As Delysid stocks dried up, new producers picked up the slack. That year Augustus Owsley Stanley bought his first tranche of precursor chemicals and began home-manufacturing LSD for Ken Kesey, the Merry Pranksters and the Grateful Dead. The psychedelic era was well and truly under way.

a version of this article first appeared on PROHBTD

with images from the Hans Marti Archive