The Art of Mind Control

As the digital age settles in around us, the influencing machine is quietly making itself at home in the mainstream of our techno-hungry culture. Twenty years ago, the idea of a covert device that uses futuristic technology to send messages and control minds was confined to a handful of cults and subcultures: aficionados of the paranoid sci-fi of Philip K.Dick, or of a samizdat conspiracy literature where mind control was occasionally proposed as the hidden hand that unifies the disparate narratives of alien abductions and controlling elites. Now, for every twelve year old who has seen The X-Files, The Matrix or a thousand film, TV and comic spin-offs, the influencing machine needs no explanation, and the Internet hums with stories of subliminal messaging, mysterious implants and military mind control programmes. The influencing machine is even moving beyond familiarity into parody: the character who wears a tinfoil hat to deflect its malign controlling rays has become a comedy cliché, a crude shorthand for paranoia and by extension for madness in general.

This is a stereotype that recalls that the influencing machine, for all its recent incursions into popular culture, has its roots in clinical psychiatry and psychoanalysis, where the term was originally coined nearly a century ago to describe a delusion observed in those suffering from the bizarre mental condition that was shortly to be christened ‘schizophrenia’. But the first representation of an influencing machine can be traced back a century further still, to the prototype for all these spectral-cum-mechanical devices, the ‘Air Loom’, which was detailed in eerily precise technical drawings between 1800 and 1810 by a Welsh tea-broker named James Tilly Matthews.

Matthews was, at this time, confined in the Royal Bethlem Hospital – Bedlam – as an incurable lunatic, although he claimed (and with some good evidence) that he was being held illegally as a political prisoner. The Air Loom, he maintained, had him in its invisible grasp, racking him with agonising pains and twisting his thoughts into gibberish. His elegantly rendered plans showed a machine fuelled by barrels of magnetised gas and ‘putrid effluvia’, and powered by Leyden jars and windmill sails, that wove invisible mesmeric currents which, beamed at a human target by its sinister operators, assailed the victim’s body with tortures such as ‘lobster-cracking’ and ‘apoplexy-working with the nutmeg-grater’, and filled his mind with alien voices and nightmarish visions.

Matthews was, at this time, confined in the Royal Bethlem Hospital – Bedlam – as an incurable lunatic, although he claimed (and with some good evidence) that he was being held illegally as a political prisoner. The Air Loom, he maintained, had him in its invisible grasp, racking him with agonising pains and twisting his thoughts into gibberish. His elegantly rendered plans showed a machine fuelled by barrels of magnetised gas and ‘putrid effluvia’, and powered by Leyden jars and windmill sails, that wove invisible mesmeric currents which, beamed at a human target by its sinister operators, assailed the victim’s body with tortures such as ‘lobster-cracking’ and ‘apoplexy-working with the nutmeg-grater’, and filled his mind with alien voices and nightmarish visions.

In a perverse but inspired move, the installation artist and crop circle pioneer Rod Dickinson has recently turned Matthews’ hallucinatory blueprints into reality. The result is a huge and inscrutable piece that fills a large gallery space, towering ominously over the spectator. On one level it’s a clean, sober and ‘authentic’ assemblage of eighteenth-century technology, with oak panelling, brass fittings, hooped barrels and tanned leather tubes: a period piece, yet also brand new, as if fresh off the assembly line and poised to hiss and rumble into life. On another level, though, the way that its vast scale dominates the viewer generates a frisson of the claustrophobia that Matthews himself felt when this uncanny device intruded into his own reality, projecting the voices of its malign operators from his dreams into his waking life.

In a perverse but inspired move, the installation artist and crop circle pioneer Rod Dickinson has recently turned Matthews’ hallucinatory blueprints into reality. The result is a huge and inscrutable piece that fills a large gallery space, towering ominously over the spectator. On one level it’s a clean, sober and ‘authentic’ assemblage of eighteenth-century technology, with oak panelling, brass fittings, hooped barrels and tanned leather tubes: a period piece, yet also brand new, as if fresh off the assembly line and poised to hiss and rumble into life. On another level, though, the way that its vast scale dominates the viewer generates a frisson of the claustrophobia that Matthews himself felt when this uncanny device intruded into his own reality, projecting the voices of its malign operators from his dreams into his waking life.

When Matthews conceived the Air Loom, the notion of a machine that controlled human minds was, as far as we know, unprecedented; but as the nineteenth century progressed, doctors and psychiatrists began to see patterns in the way that some mental patients co-opted new technologies into their paranoid imaginings. ‘The insane are quick to catch at new scientific notions to explain their delusions’, noted the doctor William Ireland in 1886. ‘Complaints of being electrified and being magnetised against their will have long been common; and since the invention of the telephone , they have said that there are telephones in their rooms, or that people use these instruments to torment them’ . The Air Loom resonates powerfully through the overheated clinical literature of the fin-de-siècle. The playwright August Strindberg, during his baroque nervous breakdown, was convinced that an electrical machine concealed under his bed controlled his dreams while he slept; and the celebrated paranoiac Daniel Paul Schreber’s memoirs give a minute account of the cosmic rays that assailed him with ‘miracles’, even remaking his body into that of a woman.

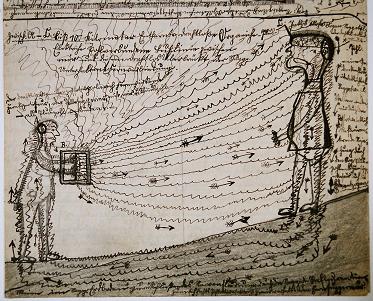

It was during this period, too, that the artwork of patients undergoing similar experiences began to be collected. Hans Prinzhorn preserved several works by Jacob Mohr, who was confined in Heidelberg’s psychiatric clinic in the years around 1910, producing extraordinary diagrams filled with black boxes radiating electric currents and hypnotic rays. In the scrambled but oddly techno-savvy text that accompanies them Mohr presents himself at some points as the omnipotent ‘Ruler of the World’, at others as the helpless victim of a ‘wireless-organic-positive-polar’ device that torments and paralyses him.

It was during this period, too, that the artwork of patients undergoing similar experiences began to be collected. Hans Prinzhorn preserved several works by Jacob Mohr, who was confined in Heidelberg’s psychiatric clinic in the years around 1910, producing extraordinary diagrams filled with black boxes radiating electric currents and hypnotic rays. In the scrambled but oddly techno-savvy text that accompanies them Mohr presents himself at some points as the omnipotent ‘Ruler of the World’, at others as the helpless victim of a ‘wireless-organic-positive-polar’ device that torments and paralyses him.  The remarkable and contested work from the same period by Rosegg Mental Hospital patient Robert Gie is now held at the Musée de l’Art Brut in Lausanne. Gie’s figures, like Mohr’s, are also surrounded by waves and currents, which are often depicted penetrating the sensitive areas of their feet, palms and palates; Gie often wore a handkerchief over his face to prevent these emanations from entering him while he worked.

The remarkable and contested work from the same period by Rosegg Mental Hospital patient Robert Gie is now held at the Musée de l’Art Brut in Lausanne. Gie’s figures, like Mohr’s, are also surrounded by waves and currents, which are often depicted penetrating the sensitive areas of their feet, palms and palates; Gie often wore a handkerchief over his face to prevent these emanations from entering him while he worked.

In 1919 the gifted, maverick and ultimately tragic Victor Tausk, an early disciple of Sigmund Freud , developed an ambitious and complex framework to describe and account for this type of delusion. His paper On the Origin of the Influencing Machine in Schizophrenia coined the enduring term for such devices (originally in its German form, ‘Beeinflussingsapparat’) and related them to the schizophrenic patient’s sense of disconnection from the body, and their merging of internal sensations and external stimuli. The patient who prompted Tausk to these insights was a 30-year-old philosophy student named as Natalija A., who confided to him that her thoughts and dreams were being manipulated by an electrical device operated by a cabal of doctors in Berlin. (Her case is the inspiration for a recent installation by contemporary New York artist Zoe Beloff, which uses a 3-D optical system to project Natalija’s phantom body into virtual space and a sensor device to trigger a disturbing melange of film loops, mostly sequences from 1920s medical training films, within its organs.)

Like Matthews’ blueprints, many of the pieces from the early twentieth century are realised with unnerving precision, some by patients who were skilled and practised draughtsmen before their confinement. Joseph Schneller, for example, was a technical draughtsman before his admission to the Eglfing-Haar mental hospital in 1907, at which point he started drawing elegant and chilling images of humanoid machines emitting spectral rays while performing sinister and perverted acts – typically squeezing women into tight rubber clothes that distort their bodies, or administering enemas and flagellations to nurses in elegant art nouveau tiled bathrooms.

Like Matthews’ blueprints, many of the pieces from the early twentieth century are realised with unnerving precision, some by patients who were skilled and practised draughtsmen before their confinement. Joseph Schneller, for example, was a technical draughtsman before his admission to the Eglfing-Haar mental hospital in 1907, at which point he started drawing elegant and chilling images of humanoid machines emitting spectral rays while performing sinister and perverted acts – typically squeezing women into tight rubber clothes that distort their bodies, or administering enemas and flagellations to nurses in elegant art nouveau tiled bathrooms.

Other artists found their images concealed in the world around them. The former sign-painter and decorator Friedrich Leonardt Fent, for example, who was transferred to mental hospital in 1910 while serving a prison term for sexual abuse of his step-daughter, created his oeuvre by taking the artwork from advertisements and book jackets and twisting it to reveal the influencing machines that were hidden within the image.  Thus a prancing devil from a newspaper ad for storage batteries is given a mysterious black box which transmits the disembodied voices that Fent is hearing in his head; and the cover of a popular book on hypnosis is customised to include a figure trapped in a hypnotic beam almost identical to the one so carefully inked by James Tilly Matthews one hundred years earlier. Fent was also tormented by doctors who he refers to as ‘Dr. Know-All’ and ‘Dr. Rönthgen’ who ‘treated’ him with sinister techniques such as ‘hypnosis-auto-suggestion’ and ‘electro-technology’.

Thus a prancing devil from a newspaper ad for storage batteries is given a mysterious black box which transmits the disembodied voices that Fent is hearing in his head; and the cover of a popular book on hypnosis is customised to include a figure trapped in a hypnotic beam almost identical to the one so carefully inked by James Tilly Matthews one hundred years earlier. Fent was also tormented by doctors who he refers to as ‘Dr. Know-All’ and ‘Dr. Rönthgen’ who ‘treated’ him with sinister techniques such as ‘hypnosis-auto-suggestion’ and ‘electro-technology’.

When the first X-ray image – of the living skeleton inside the hand of William Roentgen’s wife’s – was splashed across the front pages of the world’s press in 1896, it was claimed by many, not just the insane, as evidence for an invisible body that had until now remained concealed from the world of outward appearances. Similarly, when radio began to emerge as a household technology in the 1920s, it too was claimed by spiritualists as evidence that ‘brain waves’ or‘mind rays’ could be sent and received across large distances. In 1924, just as radio was beginning to penetrate the  high street, Johanna Wintsch, a patient at the Burghölzli asylum in Zurich, produced a work of embroidery which she called ‘Je Suis Radio’. Stitched in scintillating colours onto cream-coloured cloth, it shows a lattice of waves and vibrations similar to many others here. Many of the subjects describe these rays and lattices as representing a heightened state of cosmic communication in which supernatural energies flow from the subject out into the universe, where they are woven into a vast nervous system that binds the artist with the infinite.

high street, Johanna Wintsch, a patient at the Burghölzli asylum in Zurich, produced a work of embroidery which she called ‘Je Suis Radio’. Stitched in scintillating colours onto cream-coloured cloth, it shows a lattice of waves and vibrations similar to many others here. Many of the subjects describe these rays and lattices as representing a heightened state of cosmic communication in which supernatural energies flow from the subject out into the universe, where they are woven into a vast nervous system that binds the artist with the infinite.

Over the last century, such visions have increasingly diffused into the mainstream of our culture, amplified and recycled through cyberspace and the Hollywood dream machine; but they are still generated by the outsiders with whom they originated, and in endlessly surprising forms. The Prinzhorn Collection in Heidelberg houses an installation representing the half a million sheets of A4 paper produced by Vanda Vieira-Schmidt (1949-), who was discharged from a psychiatric hospital in 1995 and released into sheltered accomodation in Berlin. She believes that she witnessed demonic operators with portable uranium devices on the underground, torturing and even murdering passengers with electricity and ‘uranium hits’. Since her release, she has been drawing diagrams and magical sigils on pieces of paper at a rate of up to a thousand a day. Now, whenever any violence breaks out anywhere in the world, it can be controlled; the Ministry of Defence, indeed, could use her drawings to mediate in global conflicts. This work has helped to restore her peace of mind, and, she feels, a broader ‘peace on earth’ – a goal that would have been well understood by James Tilly Matthews, a passionate peace activist whose confinement in Bedlam was the culmination of his reckless and tragic attempts to prevent war between Britain and France.

Much of this material is now collected in the fine bilingual catalogue that was produced to accompany last year’s exhibition of influencing machine art at the Prinzhorn Collection , and that brings the materials on the influencing machine together in a way that has never been done before, and is unlikely ever to be bettered. Studies in this area have typically been hamstrung by the fact that most of the material on James Tilly Matthews and the Air Loom is unfamiliar to German speakers, while that on Victor Tausk, Hans Prinzhorn and the ‘Beeinflussungsapparat’ has rarely made its way back into English. Here, they combine to illuminate the trajectory of a phenomenon that originated two hundred years ago as monstrous specimen from the far shores of madness, but is rapidly coming into focus as a defining myth for our technological future.

This article first appeared in Raw Vision (2007)

Images courtesy of the Prinzhorn Collection

The catalogue of the Prinzhorn Collection’s exhibition ‘The Air Loom and Other Dangerous Influencing Machines’ (2006) is available from www.wunderhorn.de

Images of Rod Dickinson’s Air Loom are archived at www.theairloom.org

RELATED BOOK: The Influencing Machine