‘The Colony of the Mad’

The history of Geel, and the future of mental healthcareHalf an hour on the slow train from Antwerp, surrounded by flat, sparsely-populated farmlands, Geel strikes the visitor as a quiet, pretty and typical Flanders market town. But its story is unique. For over 700 years its inhabitants have taken the mentally ill and disabled into their homes as guests or ‘boarders’, sharing their lives with them for years, decades or even a lifetime. At times they have numbered in the thousands, arriving from all over Europe and beyond. There are several hundred in residence today.

‘Mentally ill’ is a term rarely heard among the people of Geel: even words such as ‘psychiatric’ and ‘patient’ are typically hedged in with finger-waggling and scare quotes. The family care system, as it’s known locally, is resolutely non-medical: when boarders meet their new families they do so, as they always have, without a backstory or clinical diagnosis. If a word is needed to describe them, it’s often a positive one such as ‘special’, or at least a neutral one like ‘different’. (This is in fact more accurate than ‘mentally ill’, since the boarders have always included some who would today be diagnosed with learning difficulties or special needs.) But the most common collective term is ‘boarders’, which defines them at the most pragmatic level by their social, not mental condition: these are people who, whatever their diagnosis, have come to live here because they’re unable to cope on their own and have no family or friends who can look after them.

The code of conduct for families evolved in the distant past without any external or professional guidance. A boarder is essentially treated as a member of the family: involved in everything and particularly encouraged to form a strong bond with the children, a relationship seen as beneficial to both parties. Their behaviour is expected to meet the same basic standards as everybody else’s, though it’s also understood that they may not have the same coping resources as others. Odd behaviour is ignored where possible, and dealt with discreetly when necessary. Those who meet these standards are ‘good’; others may be described as ‘difficult’, but never ‘bad’, ‘dumb’ or ‘crazy’. If they’re unable to cope on this basis, they will be readmitted to the hospital: this is inevitably seen as a punishment, and everyone hopes the stay ‘inside’ will be as brief as possible.

The people of Geel don’t regard any of this as therapy: it’s simply ‘family care’. Yet throughout its long history many, both inside and outside psychiatry, have wondered whether this is not only a form of therapy in itself, but perhaps the best form there is. However we might categorise or diagnose their conditions, and whatever we believe their cause to be, the ‘mentally ill’ are in practice those who have fallen through the net, who have broken the ties that bind everyone else into a social contract, who are no longer able to connect. If these ties can be remade and the individual reintegrated into the collective, does not ‘family care’ amount to therapy – even, perhaps, the closest we can approach to an actual cure?

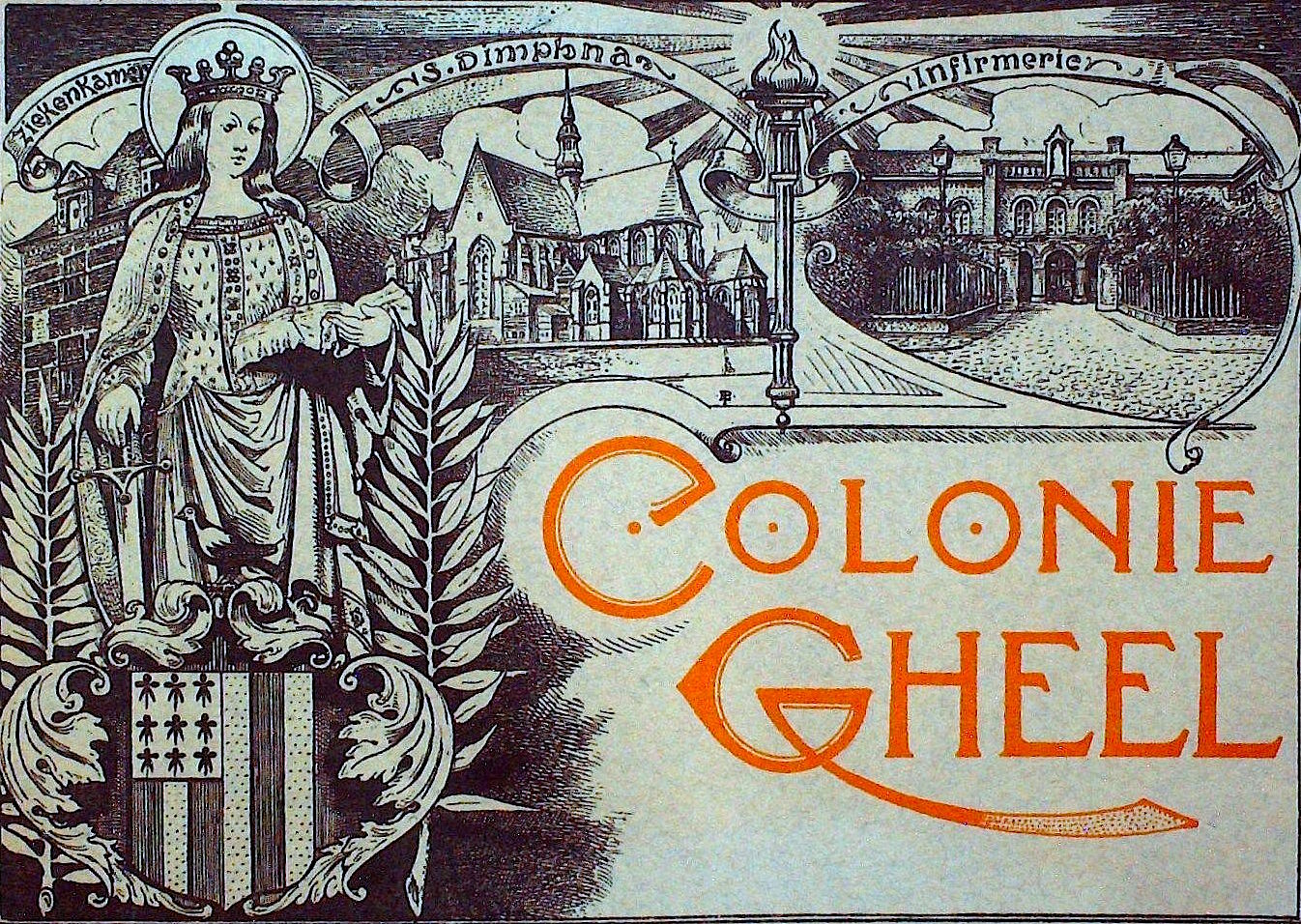

The origins of the Geel story lie in the thirteenth century and the martyrdom of St. Dympna, a legendary seventh-century Irish princess whose father, a pagan king, was driven mad with grief by the death of his Christian wife. In his derangement he demanded his daughter marry him to replace her, and Dympna fled to Europe to escape his incestuous passion.  She holed up in the marshy flatlands of Flanders, where her father finally tracked her down; in Geel, she refused him once more and he beheaded her. Gradually she became revered as a saint with powers of intercession for the mentally afflicted, and her shrine attracted pilgrims and tales of miraculous cures.

She holed up in the marshy flatlands of Flanders, where her father finally tracked her down; in Geel, she refused him once more and he beheaded her. Gradually she became revered as a saint with powers of intercession for the mentally afflicted, and her shrine attracted pilgrims and tales of miraculous cures.

In 1349 a church was built on the outskirts of Geel around St. Dympna’s shrine, and in 1480 a dormitory annex was added to accommodate the growing number of pilgrims. But they soon overflowed their allotted space, and the townspeople started to house them in their homes, farms and stables. By the Renaissance Geel had become widely known as a place of sanctuary for the mad, who arrived and were welcomed for reasons that combined the spiritual and the opportunistic. Pilgrims were drawn by hopes of a cure, though in some cases it seems that families and local villages used the pilgrimage as a chance to abandon troublesome relatives they couldn’t afford to keep. The people of Geel absorbed them all as an act of charity and Christian piety, but also put them to work as free labour on their farms.

This arrangement continued through to the nineteenth century when attitudes to mental illness were transformed by the arrival of psychiatry and the asylum hospital. For the first generation of psychiatrists ‘the Geel question’, as it became known, polarised opinions about the social and medical revolution they were attempting to bring about. For many the system was a dismal relic of the Middle Ages where the mad were condemned to a life of drudgery and neglect under the lax or non-existent oversight of the church. Shut away from the modern world in quasi-feudal isolation, they were denied the benefits of medical expertise and any chance of genuine treatment.

For others, though, Geel was a beacon of the progressive ideas that came to be known as ‘moral management’: the therapeutic benefits of freeing the insane from their chains and madhouses and providing them with fresh air, occupational therapies and the chance to patch themselves back into normal life. Philippe Pinel, the founding father of French psychiatry legendary for ‘striking the chains off the mad’ at the Salpetrière asylum in Paris, declared that ‘the farmers of Geel are arguably the most competent doctors; they are an example of what may turn out to be the only reasonable treatment of insanity and what doctors from the outset should regard as ideal’. His student Jean-Etienne Esquirol, who became the next generation’s leading reformer of mental hospitals, visited Geel in 1821 and was astonished by the sight of hundreds of lunatics wandering freely and calmly around the town and countryside. He praised the tolerance of a system where ‘the mad are elevated to the dignity of the sick’.

In 1850 Belgium established state provision for the treatment of lunatics, into which Geel was integrated in an arrangment that combined elements of both past and future. Oversight of the family care system was transferred from church to government and a modest state payment for families was instituted, in return for which families were inspected and regulated by the medical authorities. Restraint and corporal punishment were banned: under the church system any crimes committed by a boarder had been the responsibility of the family, who had sometimes resorted to chaining and beating individuals who were violent or difficult to control. The town and its environs were officially designated as an open-air asylum, a ‘colony of the mad’.

In 1861 a hospital was built on the outskirts of town: a two-story building with an elegant portico and large arched windows, designed in every detail to resemble a country mansion rather than a prison. Boarders, arriving now as wards of state, were housed and assessed here before being entrusted to families. Those inappropriate for family care, such as the violent or suicidal, were sent to asylums; the rest could be returned to the hospital if they became unmanageable.

Medical supervision brought great improvements, but the directors of the new hospital remained committed to the principle that it should support rather than replace Geel’s unique regimen. In the terminology still used by boarders and townspeople today, ‘inside’ – the world of the hospital – was a resource whose use should be kept to a minimum, and ‘outside’ – the wider community – was preferred wherever possible. Three bathhouses were built around the town which boarders were required to attend once a week, ostensibly for hygiene and health checks but also as a chance for a conversation with someone outside the family sphere. Performing this supervision ‘outside’ rather than ‘inside’ meant that, for most boarders, the smell of the hospital and the sight of asylum wards, straitjackets and high-walled exercise yards vanished from their lives.

The reformed system became a source of great professional and local pride. Doctors and psychiatrists from across Europe and America came on fact-finding missions; dozens of towns in Belgium, France and Germany adopted versions of the ‘Geel system’, some of which still survive. In 1902 the ‘Geel question’ was officially settled by the International Congress of Psychiatry, who met in Antwerp to declare it an example of best practice to be emulated wherever possible. Similar systems were established as far away as Japan; in Scotland, some asylums that already operated open-door policies began to board out their patients, earning them the nickname ‘Geels of the north’.

Through the twentieth century the system prospered and expanded, and the town’s fame spread. With the growth of state asylums, families across Belgium were faced with the choice of having their relatives ‘put away’ for life in grim institutions or sending them to Geel,  where handsome promotional photographs and brochures showed them working the fields, attending harvest festivals and church services and sleeping in regularly-inspected private bedrooms with cots and linen sheets. So many boarders arrived from the Netherlands that their families built a Protestant church in town for them. One wealthy family even took in a Polish prince, who came with his own butler and carriage.

where handsome promotional photographs and brochures showed them working the fields, attending harvest festivals and church services and sleeping in regularly-inspected private bedrooms with cots and linen sheets. So many boarders arrived from the Netherlands that their families built a Protestant church in town for them. One wealthy family even took in a Polish prince, who came with his own butler and carriage.

By the late 1930s there were almost 4000 boarders among a native population of 16,000. Across Belgium the town became famous for its eccentricity and often the butt of coarse humour (‘Half of Geel is crazy, and the rest are half crazy!’), but in Geel itself normal life was little affected, and the local jokes tended to revolve around how frequently locals and boarders were confused and how hard it was to tell the difference. Boarders were well aware that disruptive public behaviour might result in being sent back ‘inside’; the problem was more commonly the opposite, that they became overly timid for fear of drawing attention to themselves.

In recent decades the ‘two-layered system’ – family care supported by a medical safety net – has been constantly adjusted to reflect developments in psychiatry. The most abrupt shift came in the 1970s, as the asylums emptied and mental healthcare was reconceived to become more flexible and extend further into the community. Antipsychotic and antidepressant medications, central to the new treatment model, were initially resisted by many families who felt they would turn boarders into medical outpatients, but they soon proved their worth in helping to manage the worst of the depressions, crises and public incidents.

Although these were all changes for the better, they coincided with a precipitous and perhaps terminal decline in the centuries-old system. Today there are around 300 boarders in Geel: still a considerable number, but less than a tenth of its pre-war peak and falling fast. While many locals believe family care will endure, it has become a markedly smaller part of town life and others suspect that this generation will be last to maintain it.

Why is this deeply rooted and universally praised system suddenly on the point of disappearing? There are many answers, some obvious, some less so. The limiting factor is not demand but supply: the number of families able or willing to take on a boarder. Few still work the land or need help with manual labour, as they did in times gone by; these days most are employed in the thriving business parks outside town, hosts to multinationals such as Estée Lauder and BP. Dual-income households and apartment living mean that most families can no longer offer care in the old-fashioned manner.

The tradition remains a source of pride, and many credit it with giving Geel a broad-minded and tolerant ethos that has made it attractive to international businesses and visitors: these days it’s probably best known in the wider world for its annual reggae festival. But the town is no exception to the march of modernity and its irreversibly loosening social ties. Modern aspirations – the increasing desire for mobility and privacy, timeshifted work schedules and the freedom to travel – disrupt the patterns on which daily care depends. Modern prosperity is also a disincentive: it was always the poorer families, who counted on the free labour and state payments to lift them above subsistence, who took on most of the burden.

The decline of the system is not altogether to be lamented. Psychiatry has met the town halfway: the choice is no longer limited to the stark alternative of Geel or the asylum. Care in the community, of which the town was once the leading example, has become the norm. For most mental health service users, the combination of medication and community mental health teams has made the line between ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ more porous, with ‘outside’ the preferred option for doctors and patients alike, on grounds of both quality of life and cost.

The boundaries have blurred in Geel too: over half of boarders now have some form of service provision such as day care, therapy or supervised work programmes. The old system is hard to maintain within the institutional logic of modern mental health care. Families come under pressure to be trained in therapy or psychiatric nursing as part of their duty of care to their boarders, but many insist that they aren’t clinicians and don’t want the responsibility for their boarders’ medication regimes or other medical issues. In accordance with their patient rights, boarders are now given their own diagnoses; they are free to share them with families or not as they choose, but either way the inevitable effect is to relegate family care to a residential arrangement. Within the family home they may still be boarders, but outside it they are now ‘patients’ or ‘clients’.

In 1983 a modern psychiatric clinic was opened beside the old hospital. Today its sleek brick-and-glass campus is home to an extensive complex of juvenile, adult and senior residential care units that operates on a far larger scale.

Funding for family care is managed and disbursed from within the new hospital. The state now pays around €40 per day for boarders, of which only half is passed on to the families: for most these days, hardly a financial incentive. Yet the famous ‘Geel system’ still has its champions – doctors, families and boarders alike – for whom it remains a pointer to future marriages of medical and community care. The old hospital buildings have been renovated to house a day centre and a well-appointed art studio and gallery; among the modern hospital blocks a free range chicken enclosure supplies a traditional flavour of farming life.

When the antipsychiatry movement emerged in the sixties and seventies many of its proponents, like the nineteenth-century moral and religious reformers before them, used the story of Geel to argue that psychiatry and its institutions should have no place in the treatment of the mentally unwell, and indeed create many of the problems they purport to solve. There are many clear examples in Geel’s long history of medicine’s benefits: eliminating the use of restraints and physical punishment, stepping into chaotic situations where families are no longer able to cope, providing medications that can transform lives. Its story does, however, suggest that psychiatry could be cast in a rather different role: one in which the community is at the centre of mental healthcare and the medical professions on its periphery, a discreet ‘inside’ to be deployed only when ‘outside’ resources are exhausted.

But this would demand a reform not simply of medicine but of society itself. It’s ironic but probably not coincidental that the need for a community response to mental illness is becoming obvious just as the structures that might supply it are failing. If mental illness is in practice a condition that has exhausted the capacity of the individual and the social support available to them, it will manifest more intensely in an atomised society where its insoluble problems devolve onto the sufferer alone. To take up these problems on behalf of others demands vast resources of time, attention and love: all too often, more than their own family and friends can give or the state can provide. As mental ill-health proliferates and outpaces the resources available to psychiatry to manage it, Geel’s story offers a vision, in equal parts sobering and inspiring, of what the alternative might look like.

Versions of this piece have appeared on aeon.co and in The Psychologist

Contemporary photos of Geel © the author